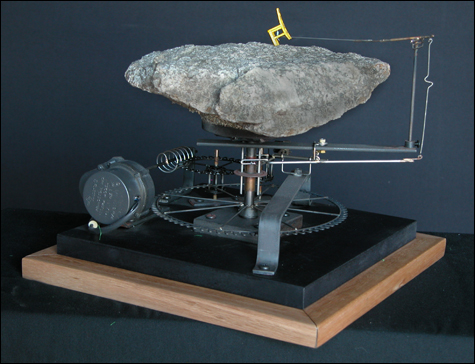

BUT DOES IT TALK? "Thinking Chair," by Arthur Ganson. |

| "Machines Contemplating Time" | sculpture by Arthur Ganson | Through March 6 | artist talk noon Feb 7 | at ICA at MECA, Porteous Bldg, 522 Congress St, Portland | 207.879.5742 |

Arthur Ganson’s work makes you slow down and consider how things are done. In his show "Machines Contemplating Time" at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art we first see the outcome of the machine’s actions and then are led to contemplate how this action comes about. His work inspires meditations on the mechanical style of the industrial revolution as well as the celestial mechanics of Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe. The pieces are exercises in the poetry of engineering, or perhaps the engineering of poetry.A good example is "Thinking Chair." A flat piece of fieldstone about a foot or so across is held up by a metal structure that also supports a complex but very straightforward mechanism. The machine "walks" a tiny yellow chair around the top of the stone. How this happens is at the heart of Ganson’s work.

The machine is made of open metalwork, including spur gears, worm gears, couplings, cams, and linkages all made of steel wire that has been hand-shaped and brazed or bolted together. Ganson’s mechanism takes the simple high-speed output of a small electric motor and transforms it into a number of interrelated intricate motions. The structure that holds up the little chair above the rock does a slow orbit around the rock’s perimeter, carrying the chair along its path. Another mechanism rocks and tips the chair to give it its walking motion.

Ganson reveals the clockwork of his little universe, allowing us to follow the train of events from the erratic-seeming motion of the chair back to the simplicity of its prime mover, the motor. Renaissance astronomers and, later, Isaac Newton, were trying to elucidate the nature of just such a clockwork that they thought was driving the motion of the planets. Our task is similar, but a little easier. We can see what kinds of angels are pushing the planets around.

In "Accumulation of Time" a red thread is drawn from a spool in the bottom section of the mechanism up through a long tube and out through an arched arm at the top of the tube. The thread passes over a pulley and descends. The tube is also the support column for the machinery, a worm and spur gear arrangement that slows down the force from the motor in the bottom and transfers it to the pulley. At the end of its travel the thread accumulates in a pile at the base of the sculpture, having transited from order to disorder.

The action of the machinery is readily apparent, but the motion of the thread is too slow to see, like the movement of a minute hand of a clock. The process is unambiguous but virtually invisible. Things are turning but the results can be best seen by returning to see it at intervals. The simple arithmetic of gears becomes the calculus of duration.

The strength of these pieces derives from the gentle nature of their inherent allusions. Ganson suggests rather than asserts. The looms and mills of the industrial revolution employed the same kinds of engineering used in these pieces, which lends them a sense of history. The logical path that he invites us to follow is as direct and unambiguous as deductive reasoning can be: if this wheel is turned this way, the result will be that.

Yet the end results of the mechanical actions, a cloth rising and being gently blown in "The Transmutation of Cloth" or the soft, bird-like billowing of pieces of paper lifted by cams in "Machine with 22 Scraps of Paper" are poetic allusions, mysterious and almost mystical.

Ken Greenleaf can be reached at ken.greenleaf@gmail.com.