|

The Herald stands alone, and Liberty Group Publishing becomes a major local media player in a dramatic three-part newspaper deal.

|

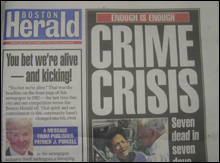

“You bet we’re alive — and kicking!” declared the headline on Herald owner Pat Purcell’s feisty message to readers on Monday. (That phrasing — no accident — is a reprise of the famous “You Bet We’re Alive” Herald headline announcing the paper’s lifesaving sale to Rupert Murdoch in 1982.)

But if the Herald splash was that Purcell was keeping the troubled tabloid he has owned for a dozen years, the bigger story was that Boston’s newspaper landscape has been dramatically and irrevocably altered by a three-way deal that broke so suddenly last Friday that some of Purcell’s employees learned about it on the Boston Globe Web site.

In a widely anticipated move, Purcell survived by agreeing to sell his profitable suburban-oriented Community Newspaper Company (CNC) chain of more than 100 publications, including four dailies, to the Illinois-based Liberty Group Publishing for, according to the Globe, about $225 million. Liberty then doubled down, swooping in to pick up the Enterprise NewsMedia collection of the Patriot Ledger in Quincy and the Enterprise in Brockton, and the 23-paper MPG chain of South Shore weeklies, all for a reported $165 to $175 million.

For years, local media operators — ranging from Fidelity Investments when it owned CNC to Purcell himself — had coveted the potentially potent combination of the CNC papers and the Enterprise outlets. And with good reason. Liberty holdings now blanket the eastern part of the state like a February blizzard and encircle the Globe.

In the end, the big prize was snatched by a largely unknown eight-year-old Illinois company — one that has never operated in Massachusetts — with an undistinguished track record and a history of buying monopoly papers in small towns. Suddenly, Liberty — soon to be renamed GateHouse Media — has control of a big chunk of the local-media chessboard. And no one seems quite sure what to make of it.

“One assumes, since they own small-town dailies, they pretty much have the market to themselves,” says newspaper consultant John Morton. “They’re small-town newspapers: they don’t usually get on the radar screen.”

Given that many of its papers have a circulation of less than 20,000, the Massachusetts acquisitions are a “big bite” for Liberty. Ventures one veteran media observer: “This is a huge step up for them.”

But if the Liberty acquisition has raised more questions about the future of Massachusetts journalism than it has answered, the Herald’s status is, likewise, far from permanently resolved.

Purcell came out slugging in Monday’s paper, declaring in his message: “So let me dash the fondest hopes of the politicians, the prognosticators and our competitors at the Globe. The Boston Herald is here to stay.” But while the Liberty deal may have cleared debt and given Purcell breathing room, few think he can make the paper work without cutting more costs and perhaps trying something more dramatic — such as a free-distribution model.

“I don’t ever predict the death of newspapers. [But] the history of the newspaper business tells us that second papers in the Herald’s position are a dying breed,” says Morton.

Or, as one Herald employee succinctly put it: “I think probably we’ll have to reinvent ourselves somehow.”

Give Me Liberty

Several years ago, a story in Crain’s Chicago Business pithily described Liberty as “the largest newspaper empire you’ve never heard of.” Based in Northbrook, Illinois, the company owns more than 270 papers (including 64 dailies) in 15 states.

A fairly typical Liberty publication might be the Wayne Independent, a 128-year-old paper based in the northeastern corner of Pennsylvania, with a circulation of about 4500; it’s the only daily in the county. Stories about a controversy over high-voltage lines and a borough-hall open house get significant play (at least on the Web site). When asked about the size of his editorial staff, a wary publisher told me it was none of my business.

According to one journalist who covered the company, Liberty had a reputation as “classic bean counters. They didn’t have much of a journalistic reputation at all.” They were “known for running these skeleton crews,” he says. (Liberty officials did not return calls seeking comment.)

But some things have recently changed. Liberty was bought about a year ago by an affiliate of the Fortress Investment Group. Liberty CEO Mike Reed recently came aboard from the Alabama-based CNHI (Community Newspaper Holdings Inc.), where he was instrumental in orchestrating that company’s purchase of the family-owned Eagle Tribune Publishing Company last summer.

“What you really need to look at is the track record of CNHI, which has a sterling reputation,” says Michael Gilligan, a general partner at Heritage Partners, which has been the owner of the Enterprise papers. “Mike is an industry veteran with a lot of experience dealing with weeklies and smaller suburban dailies, with Kirk as the best possible operator to put this together.”