|

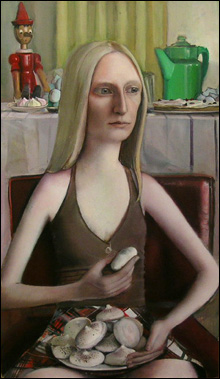

HANNAH WITH MERINGUES: Shira Avidor has figured out that the most surreal things are normal scenes that are ever so slightly off.

|

Put the words “government” and “art” together and it’s hard not to imagine a result as exciting as soggy oatmeal. Still when I heard that Boston Sculptors Gallery’s “Mass 3D” exhibit would feature six sculptors who won $5000 state artist grants in 2005, I was eager to go see what my tax dollars had paid for.

On one wall hang Truro sculptor Timothy Horn’s two melted-looking rococo sconces, cast in polyurethane rubber from 18th-century Chippendale patterns. The leafy candleholders appear to sprout and ooze from the ornate wall plates. And the material is a translucent yellow somewhere between urine and honey that reinforces the charmingly creepy feeling that they’re ALIVE! My tax dollars, I realized, were a down payment on a haunted house. Maybe our government is on the right track.

This prompted further thought. Our state constitution says it’s the duty of government leaders to “cherish the interests of literature and the sciences . . . to encourage private societies and public institutions, rewards and immunities, for the promotion of agriculture, arts, sciences, commerce, trades, manufactures, and a natural history of the country.” Why? Because in 1780 John Adams and his forefather pals believed this fostered the wisdom, knowledge, and virtue citizens need “for the preservation of their rights and liberties.” In other words, promoting the arts promotes democracy.

When we talk about government support for the arts, however, what we generally talk about is money. Sometimes it seems we have to choose between spending on the arts or funding more teachers and police, help for the poor, the infirm, the mentally ill. But that’s an illusion. The Massachusetts Cultural Council’s budget this fiscal year was $10.9 million — $8.5 million for grants and programs. Whereas a decade ago, the state changed the way Massachusetts’s mutual-fund industry is taxed in a way that, according to our Department of Revenue, will save the industry roughly $132.4 million this fiscal year and some $141 million the next. The real question is: how do we fairly distribute spending — whether on arts, commerce, or natural history — that goes beyond providing necessary services?

My thoughts were interrupted by a restless banging coming from a pair of mysterious metal doors in the floor in an empty corner of the gallery. These doors are always there, usually awkwardly asserting their presence under sculpture pedestals. Liz Nofziger of East Boston installed a red light that shines up through the crack between them and the recorded clanking that seems to come from far below. This is a classic minimalist move: changing the space slightly to get you to pay fresh attention to it. The banging makes you ask what’s down there. Her twist is the horror-movie styling, which is more cheesy than spooky, but it gets your attention. The knocking seeped into my head and drove me batty.

And it made Newton artist Julie Levesque’s pristine white schoolroom feel more ominous. Rows of desks face an array of white fluorescent lights. One desk bulges with papers, another buckles under a pile of books, a third seems melted by acid. Books and pencils are crusted with crystally powder. Something’s gone terribly wrong here. You’ve seen this movie before, but it’s still unsettling.

Other works are less creepy. Andrew Mobray of South Boston cuts up men’s trousers and stitches the pieces together to create what his artist statement calls “absurdly phallic” dust covers for fishing reels. The shapes are alluringly new and curious while retaining sensations of their original use. And he tickles the divide between men’s things (fishing) and women’s things (sewing). So it’s too bad it boils down to a stale fishing-rod-equals-penis gag. Somerville artist Greg Mencoff’s abstract wood sculptures are so subtly smoothed and polished that they could have fallen off some alien spacecraft. Sachiko Akiyama of Brookline aims to “describe the deeply private and mysterious psyche of the individual” with her tiny wooden heads and figures. The psyches of these carefully carved people are all apparently gloomy and blank.

So did I get my money’s worth? This isn’t the sort of government-funded art rife with smut, perversion, and blasphemy that sparks legislative hearings — unfortunately. There are pleasures to be had in these mild funhouse jolts and shocks, but what the artists talk about and how they say it won’t keep you or your state rep up at night.

In February, while wandering through some crummy hallway at Boston University, I happened upon a student’s paintings of strange glassy-eyed ladies with tables full of cookies, tarts, and cakes. In one, a skinny pretty brunette sat behind a table in an exceedingly empty room holding a candy apple. On the table stood a strawberry-topped layer cake. The woman gazed thoughtfully into the distance. Everything was a bit stretched and warped, as if seen too closely through a wide-angle lens. Something weird and intriguing was going on here that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. I jotted down the artist’s name — Shira Avidor — and later e-mailed the school but got no response. Then I got busy and forgot about the paintings, but every once in a while I remembered them and told myself I had to track down this Avidor.