|

I first read Ralph Ginzburg’s magazine Fact in 1964 — as a teenager in the New Jersey suburbs — and it was a revelation. I was not unaware of edgier literary material. I often read Evergreen Review and saw as many foreign films as New Jersey and my parents would allow. But Fact was different. It was overtly political and flagrantly provocative. It ran a long interview with George Lincoln Rockwell, the leader of the American Nazi Party, which allowed him to spew out his hatred and indict himself. It printed Ralph Nader’s first article about Detroit’s efforts to conceal the structural dangers of American cars. It ran an article exposing America’s pastime — baseball — as being nothing more than a gauzily veiled, pathological Oedipal fixation in which the mythical son tries to throw his semen at his mother, only to have it batted away by the aggressive, phallic-wielding father before she can catch it. Fact — which lasted only 12 issues — was an in-your-face “fuck you” to American mainstream culture and politics. For young, anti-social, budding-radical, future gay liberationists, this was heaven: Fact hated Nazis, cars, sports, and Republicans.

But as important as Fact was — it is the inspiration for many contemporary news outlets like 20/20, The Daily Show, and the Drudge Report — Ginzburg, who died on July 6, will always be more famous for his earlier, far more scandalous publication.

The ritzy cloth-bound quarterly, Eros, of which he published only four volumes in 1962 before it was shut down by the feds, was about all about sex. But by contemporary standards, it was a cross between the literary pretensions of the New York Review of Books, the politics of the Village Voice, and the more tasteful aspects of Hustler. Ginzburg took his cue from the 1950s quarterly Aphrodite, which was published by arch pornographer Samuel Roth — famed for the groundbreaking 1957 Supreme Court decision Roth v. United States — and sold his magazine only to mail subscribers. Ever the showman (Ginzburg was as good at PR as he was at publishing), he applied with great fanfare for bulk-mailing permits from Blue Ball, Pennsylvania; Intercourse, Pennsylvania; and Middlesex, New Jersey (ultimately, he chose the last one).

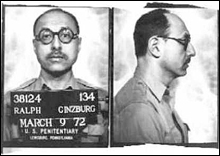

Being clever can be fatal, and by the end of 1962 Ginzburg was indicted on obscenity charges for three of his publications: Eros; Liaison, a monthly newsletter; and The Housewife's Handbook on Selective Promiscuity, a book written by noted atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair under the pen name Rey Anthony. While the publications were probably not obscene according to the law, Ginzburg was convicted because they were advertised as prurient and specifically aimed at readers’ erotic interests. As Justice William J. Brennan wrote in the Supreme Court decision, “Where the purveyor’s sole emphasis is on the sexually provocative aspects of his publications, that fact may be decisive in the determination of obscenity.” Essentially, then, Ginzburg was convicted on conspiracy to seem obscene and sentenced to five years in prison. He served only eight months.

The reality is that Ginzburg was prosecuted as much for his loud, rambunctious, and progressive anti-establishment views as for any single act. Singling out Eros was just a pretext for silencing an authentic, rebellious American voice. At a time when the Oval Office and the federal government have declared war on an increasingly unpopular press, it is more important than ever to remember Ralph Ginzburg.

ADVERTISEMENT

|