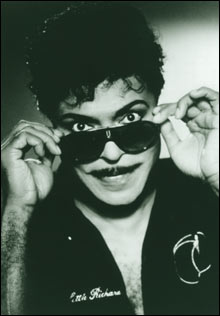

CHARISMA Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” defined Specialty’s niche between roots and mainstream.

|

In 1939 Arthur Goldberg went to Hollywood and crowned himself Art Rupe, a suitably slick moniker for an entrepreneur in the booming post-war culture industry. Not finding much room for newcomers in the movie biz, Rupe turned to music, where he could more easily locate a niche. The apt appellation he eventually gave his label, Specialty Records, described the “special” market he sought: a space for the sounds of diverse but related racial signatures, the so-called “race records” that, over the course of Specialty’s run, crossed over into the mainstream, recast as rock and roll.

Rupe’s great skill was in finding charismatic performers with catchy, crafty tunes and producing compact singles for the jukebox and home markets. Best known for Little Richard’s earth-shaking novelty, “Tutti Frutti,” Specialty found itself pushing the edges into the center from the late-’40s through the late-’50s, interweaving the resonant strains of gospel, blues, jump blues, R&B, boogie-woogie, and dance-circuit jazz just in time to reach a baby boomer, teenybopper audience thirsty for a little transgressive pop. Now, some 50 years after Specialty ruled the airwaves and dancehalls, Concord Music Group has issued a series of compilations to showcase the catalog. The label’s Specialty Profiles series offers up familiar favorites as well as delightful oddities, presenting in the process a detailed picture of a formative moment in American popular music.

The reissues run the gamut from stark to lush as they span the various genres that worked their way into what became known as rock and roll. In the label’s early years, Rupe focused on West Coast boogie and the sort of souled-up gospel — the Lord’s words animated by the Devil’s music — that would later be further secularized by the likes of Ray Charles (who himself hired Specialty’s Percy Mayfield as a chief songwriter in the ’60s). Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers were a flagship group for Rupe, despite his failure to grasp Cooke’s pop potential, afraid that embracing the singer’s secular leanings would alienate the label’s faithful. (Ironically, Rupe lost Little Richard to the church around the same time he lost Cooke to the charts.) Cooke’s and the Stirrers’ profile reveals a well-supported lead singer already mining his distinctive vocal swoops — all in the name of Jesus, of course, even as they give chills of a more down-to-earth tinge.

Stretching further into the secular market in the early ’50s, Rupe went hunting for hits in New Orleans, recording sides with Guitar Slim (including the future blues standard, “The Things That I Used To Do”) as well as Little Richard. The compilations that reach beyond these well-worn singles, including discs by Louisianans Lloyd Price, Larry Williams, and Percy Mayfield, brim with down-home style and snappy songs — if a few too many instances of grown men singing about high school girls. Accompanied by local producer-arranger Dave Bartholomew’s band (including Fats Domino on piano), Price delivers such crossover anthems as “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” and invests novelty titles and romantic clichés with more pathos than seems possible.

Similarly, Price’s cousin and former valet, Larry Williams, pushes R&B toward rock and roll on cuts such as “Bony Maronie,” propelling corny rhymes and grade-school lines with inspired singing, electric guitars, squawking saxes, and snares that snap. The punchy arrangements sound fresh next to today’s synthesized beeps and bleats, but after a while one starts to hear the assembly line at work on these discs a bit more clearly than on Specialty’s other recordings, such as those by Roy Milton or John Lee Hooker, which showcase seasoned performers improvising their way through their staple repertories.

Milton, an LA-based drummer-vocalist and bandleader and one of the first to record for Rupe, was known for big brassy blues numbers, connecting the dots between Count Basie and Louis Jordan and showing how swing jazz plays into the rock and roll gumbo. The Hooker collection shows the unique bluesman playing his signature minimal, droning blues, usually to a beat all his own, foot stomping steady while his hands and voice roam. You can’t count it 1-2-3-4, and you can’t count it 1-2-3; you just gotta count 1-1-1-1. Hooker plays like a one-man Ornette Coleman band, riffing harmolodic as he shrugs the weight of the world off his shoulders — and usually onto some woman.

It is another anonymous woman, however, who may turn in the most stirring performance of the series. Singing on a haunting demo version of Percy Mayfield’s “Hit the Road Jack” (a song the composer would later re-shape for Ray Charles’s smash), Mayfield’s unnamed female partner holds a darker-than-blue tri-tone on the chorus’s “moooooooore” in a way Ray Charles wouldn’t dare. It’s an odd little ditty that stands as a ghastly skeleton of the fleshed-out pop favorite it would become. Mayfield’s own recordings were not all huge hits, but his collection offers fine performances of well-crafted songs, including “Please Send Me Someone To Love” and “Louisiana,” showing his to be a unique voice — in the sense of his vocal “grain” as well as his compositional style. (And as if his own musical legacy were not substantial enough, he’s also the father of Curtis.)

Although these collections — especially taken as a whole — may strike the casual listener as presenting a familiar, if not downright repetitive, profile of mid-century pop, a closer listen to the range and depth of the Specialty catalog reveals some wonderfully original attempts at crafting a popular sound that could both sway the grass roots and crossover to the mainstream.