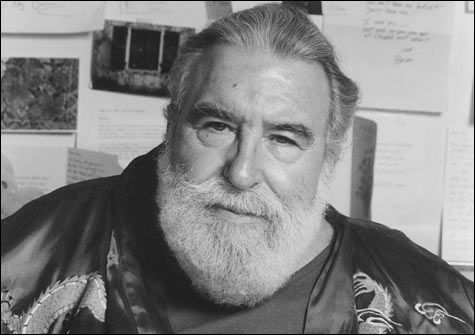

MAGIC MOMENTS: A bon vivant and songwriting genius, Pomus was always crying on the inside.

|

Even among the oddballs of the music business, Doc Pomus was unusual. Although he’d contracted polio at age seven and stood on crutches, besides being obese, diminutive, and Jewish, his first career dream was to become a famous blues singer. And he’d made a bit of a name for himself as such when he found his true niche: teaming with the considerably younger pianist Mort Shuman, Pomus became a Brill Building superstar, penning iconic hits for Elvis (“Little Sister,” “Viva Las Vegas”), Dion and the Belmonts (“A Teenager in Love”), the Drifters (“Save the Last Dance for Me,” “This Magic Moment”), and many others.

In the first bio of this remarkable “karaktuh,” as author Alex Halberstadt calls him, Pomus emerges as one of the most colorful and complex figures of the early rock-and-roll era. Born Jerome Felder in Brooklyn in 1925, he was in his mid 30s when the hits started coming. But despite having dragged himself up from poverty, he was miserable. His music of choice was the blues (he’d earlier placed songs with Ray Charles and Big Joe Turner) and jazz (Lester Young once jammed behind him), and he was convinced that his neighbors laughed behind his back when they learned he’d been responsible for providing the teen idol Fabian with the songs that made him a star.

Pomus bought a house in the suburbs, married an actress trophy wife (the first of two marriages, both ending in divorce), and counted among his friends Phil Spector and Ahmet Ertegun. But bitterness and melancholy continued to dog him. He wrote in an unpublished memoir: “I was always too fucking mad and didn’t have a chip, but a great big log on my shoulder, daring the world to get in my way or mess with me.” This from the man of whom Atlantic producer Jerry Wexler famously said, “If the music business had a heart, it would be Doc Pomus.”

It wasn’t until long after the hits, after the Beatles and Dylan made irrelevant the songwriting mills, after a 10-year writing sabbatical when high-stakes poker brought in more cash than his royalties, that Pomus began to feel comfortable in his skin. He began writing again, and though his collaborations with the likes of Dr. John and Willy DeVille never came close to the charts, he felt at home with these younger singers, who respected the same traditions he did.

By the ’80s, he had recast himself as an eccentric, ebullient man about town, dressing loudly, throwing lavish parties, turning up nightly at clubs where bouncers cleared a path for his wheelchair and set him in the prime spots. But he also became a magnet for all manner of hangers-on and hucksters, and he took to carrying a business card that read “Doc Pomus — I’ve Got My Own Problems.”

Despite the overhanging gloom, Lonely Avenue — which takes its name from the 1956 Ray Charles hit that put Pomus on the map — is anything but depressing. Halberstadt’s re-creation of period detail is rich as is his portraiture of the myriad characters who flit in and out of Pomus’s life — Muhammad Ali, Veronica Lake (with whom Halberstadt claims Pomus had an affair), Rodney Dangerfield, John Lennon. With access to family and friends, as well as to the late songwriter’s journals — he died in 1991 — Halberstadt (who never met his subject) gets at the heart of Pomus’s often conflicting personal and professional lives.

Obstacles were a way of life for Doc Pomus. The one time he attempted to meet Elvis, who’d recorded about 20 of his songs, Presley’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker, stood in his way until the singer had vacated the premises. Finally, though, he came to understand that maybe life hadn’t dealt him such a lousy hand after all.