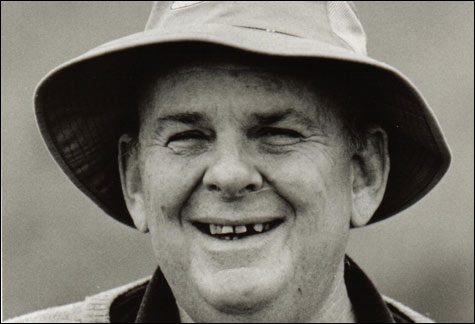

GNOMIC: Murray flits between styles with a fat man’s supernatural grace

|

|

The Biplane Houses

| by Les Murray | Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 110 pages | $23

Collected Poems for Children

| by Ted Hughes | Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 272 pages | $18

|

Les Murray and Ted Hughes, though they dwelled in each other’s antipodes, had plenty in common. Their names, for a start: sawn-off, thick-handled workingmen’s names that bespoke the ruggedness of their origins — Murray’s in a tin shack in New South Wales, Australia, Hughes’s in the unlettered valleys of West Yorkshire, England. Both were country boys, born eight years apart, who by dint of natural force and brilliance, and a faith in poetry that seemed at odds with the age, projected themselves out of the margins and into the center of national/spiritual life. In 1984 Hughes, famous already, was appointed Poet Laureate of England. In 1999, when Prime Minister John Howard announced that a new Preamble to the Australian Constitution was being drafted, he told journalists that he had enlisted the help of “the best writer in the country.” “Who’s that?” they asked. “Les, of course.” Hughes died in 1998, at the grizzled peak of his renown. Murray is still with us, huge, bald, and revered, the heavyweight of Australian poetry.

The names of Hughes and Murray have both been polarizing — the former because of a feminist death cult that attached itself to his wife Sylvia Plath in the wake of her suicide in 1963, the latter because of his ribald distaste for Modernism, political correctness, and what he calls “the Generation of ’68.” (There is some overlap here: after Hughes’s death, Murray wrote sympathetically of the Englishman’s “long torment at the hands of militants,” which he had seen for himself in 1976 when Hughes showed up to give a reading at the Adelaide Festival and was met by a mob chanting, “You murdered Sylvia!”) And without wanting to give a hostage to psychoanalysis, it must also be pointed out that behind each of these poets was the gloom of a silent father. Billie Hughes, father of Ted, never talked about what he had lived through as a soldier at Gallipoli and then Ypres: “My father sat in his chair,” wrote Hughes in his poem “Out,” “recovering/From the four-year mastication by gunfire and mud. . . . ” Cecil Murray, father of Les, was rendered near-catatonic by the death of his wife; that left his 12 year-old son to run the dairy farm by himself. “Getting near dark, I’ll go home, light the lamp/and eat my corned-beef supper, sitting there/at the head of the table. . . . ” (“The Widower in the Country”).

Hughes spent a lot of time in the scattier fringes of occultism: astrology, Ouija boards, invocations of spirits, etc. It was part of his genius to make superstitiousness look like common sense. Murray, a devout Catholic, disapproved of all this and privately disparaged Hughes as “a sensationalist and a witch.” Officially, however, the two men esteemed each other. And neither was in any doubt as to the other’s ability. As Poet Laureate, Hughes recommended Murray for the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. Murray, meanwhile, felt himself to be in Hughes’s shade whenever he wrote a poem about animals: Murray’s biographer, Peter Alexander, writes that Hughes influenced him “by reaction.” In fact, their two distinctive idioms, informal but hair-splittingly accurate, were joined in many places. Earlier this year, Farrar, Straus and Giroux published Murray’s new volume The Biplane Houses and Hughes’s Collected Poems for Children, and there is a certain parlor-game satisfaction to be had in finding lines that could have been written by either poet. A henhouse described as “a rococo excretory palace” — Hughes or Murray? A fly seen as “a freshly barbered sultan, royally armoured/In dusky rainbow metals” — Murray or Hughes? In Murray’s “Pastoral Sketches,” fresh-born foals “drop in the grass/like little loose bagpipes.” Hughes in “Cow” suggests that “The Cow is but a bagpipe/All bag, all bones, all blort. . . . ” It’s not a question of who had the image first: the two poems have the same source, the same grab bag of sounds and perceptions, the same word hoard.

Of the two books, Collected Poems for Children is more substantial; Hughes wrote a lot of poetry for kids, and from the earliest days of his career it kept pace with his “adult” work, often shedding a strange and quizzical light on his central preoccupations. What are we to make — what would a child make, for God’s sake — of the horrific Silence of the Lambs–style “My Aunt Flo”? “She rips her false face off and reveals her true one/Like a giant grasshopper. . . . And men’s dried features and women’s vital parts hang in her attic/Dusty as dry herbs.” (Hughes wrote this poem in 1961, while Plath was pregnant with their first child; that might explain Aunt Flo’s appetite for a “new-buried baby.”) But then, this ghastliness was really part of his enormous generosity as a writer: he didn’t stint his younger readers, and he didn’t spare them. Why should he? They had his highest respect, and nothing was too good (or bad) for them. Rare is the piece in Collected Poems for Children that couldn’t go head-to-head with most of Hughes’s stuff for grown-ups: the poems from Season Songs, Under the North Star and What Is the Truth?, in particular, are packed with his trademark live-wire Lawrentian immediacy. ‘The Hen/Worships the dust. She finds God everywhere./Everywhere she finds his jewels./And she does not care/What the cabbage thinks” (“Hen”).