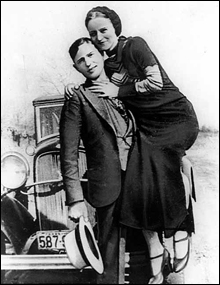

alternate version of the American Dream

during the Depression. |

From Butch Cassidy to John “the Jackrabbit” Dillinger, bank robbers have long encapsulated the American penchant for high-stakes gambling, fast getaways, and a go-your-own-way ethos of living. Even today, bank robbery remains enshrined in American pop culture as the great populist crime, with desperadoes serving as somewhat twisted contemporary Robin Hoods — robbing from the rich and living large off the loot.

But a closer examination reveals just how much the trade of bank robbers has changed. With the evolution of the Internet, the greatest spoils for maverick thieves these days are to be found online. With the accompanying rise of better bank security, hold-ups — once the province of the aristocrats of street crime — have mostly become the hardscrabble, last-ditch option of the desperate.

Not that the crime shows any signs of going away. The past few decades have seen banks opening more branches (the number of bank outlets more than tripled from 1970 to 2000), extending business hours, and designing open-floor lobbies that increasingly resemble living rooms. In catering to the customer, they’ve created more convenience — and temptation — for criminals.

Last year, there were 6985 robberies of banks, savings and loans, credit unions and armored-carrier companies nationwide, a number that tends to rise and fall with the economy, says Margot Mohsberg, a spokeswoman for the American Bankers Associa¬tion. Since experiencing a post-September 11 spike, that quantity has dropped by 9 percent, but it remains higher than it was two decades ago. Likewise in Rhode Island, the number of annual bank robberies — there were 28 in 2006 — has fallen over the past couple years, but it remains significantly higher than in the ’70s and ’80s, when it often hovered in the single digits.

But if there are more bank robberies these days, there are also more bank robbers getting caught. Prior to J. Edgar Hoover’s expansion of the FBI in the 1930s, American bank robbers were virtually home-free once they crossed state lines. Now, with changes in technology, the percentage of bank robberies that get solved is second only to murder. According to the FBI, 75 percent of robbers end up behind bars within 18 months after hitting a bank. After all, bank heists are generally committed in broad daylight, in full view of several witnesses, and usually on camera, to boot.

Bank robbing is also a high-profile crime that commands attention from law enforcement. “So when the chief tells me, ‘I want a phone call by the time I go to bed, and I want to know who did this bank robbery,’ ” says Major Stephen Campbell of the Providence police, “there’s a lot of pressure there to solve it.” Last year in Providence, police solved 95 percent of all bank robberies. Most cases are closed within weeks.

With the rise of sophisticated Internet crime gangs, the old-fashioned bank robbery seems almost an anachronism, a criminal equivalent of the eight-track tape, its persistence a perplexity. According to the US General Accounting Office, online thieves were responsible for more than $67 billion in losses in 2005, mostly through identity theft. And because the majority of these illicit operators are based overseas, in places from Zimbabwe to the Ukraine, successful extradition and prosecution is difficult, if not impossible.

By contrast, as increasingly security-savvy banks have restricted the amount of cash held by individual tellers, the typical take in a bank robbery has plummeted. In 1971, the average haul on a Rhode Island bank job was $18,500. Last year, the standard take on an in-city job was a relatively meager $2500.

It’s not bad pay for about 90 seconds’ work, although the payoff comes with considerable risk. In this regard, bank robbers still reflect a dark side of the American inclination for gambling, thrills, and instant gratification. But while the likes of Willie Sutton could net $2 million over the course of their careers, bank robbing has become a blue-collar crime. The professional bank robber is a dying breed.

Get in and get out

Last year, when 28-year-old Deaven Tucker burst into a Sovereign Bank in Providence, slinging a gun and demanding cash, he was both an anomaly and a typical modern bank robber.

Like most bank thieves in Rhode Island, Tucker’s crimes were driven by a vicious drug habit that fueled a voracious need for cash. And like most of his contemporary peers, he was caught. Yet Tucker’s case was also an exception, because while bank robberies have by no means disappeared, the old-style image of the counter-vaulting, shotgun-brandishing bank robber is increasingly a vestige of the past.