He is the epitome of traitorousness in Western culture, his name synonymous with evil and betrayal. He has also been the main single figure behind much of the anti-Semitism in Western culture. While the Jewish hierarchy and populace may have been labeled Christ killers, it was Judas the apostle who was directly responsible for his arrest and death, selling out Jesus for 30 pieces of silver.

No wonder so much attention has been paid to the discovery of the Gospel of Judas, a 26-page text translated from crumbling parchment discovered in Egypt in the 1970s, but only now published through the efforts of scholars and the National Geographic Society. The text, written decades after the now-canonical Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John, essentially recounts a conversation between Judas and Jesus. Here Judas is the favored apostle, and Jesus tells him that he “will exceed” his fellow apostles, and while he may be cursed by later generations, he will “come to rule over” them. The main plot twist here is that Jesus asks Judas to betray him — to “sacrifice the man that clothes me” — which makes Judas’s betrayal an act of fealty and love.

It’s true that Judas doesn’t come off well in the four canonical gospels. Matthew charges that Judas betrayed his spiritual leader for a paltry 30 pieces of silver (interestingly, this detail is in the Judas gospel as well), the equivalent of five months of food or the price of a slave. Both Luke and John connect Judas with Satan. John goes even further, identifying him with “night” and thus with the forces of evil (though there are also indications in John that Jesus asked Judas to betray him). And to varying degrees the four traditional evangelists blame not just Judas, but all of the Jews for the death of Jesus. “His blood shall be on us and our children,” cries a Jewish member of the mob during Jesus’s persecution, and that was good enough for Christian tradition until very recently.

But the Judas gospel and the media blitz that has accompanied it give us the opportunity to rethink Judas culturally as well as theologically.

Not only a biblical villain, Judas has grounded two centuries of anti-Semitic literature; the myth of Judas and of Jewish evil has permeated Western culture. There’s the Christ-killing Judas in early medieval mystery plays, whose shock of unruly red hair connected him with Satan. There’s the image of Judas being gobbled headfirst by Satan in the ninth circle of Dante’s L’Inferno, which also includes a region — Judecca — named after him. (The implications of “Judecca” would not have been lost on Dante’s 14th-century contemporaries, since it was also one of the names of Venice’s Jewish ghetto, where all of the city’s Jews were forced to live.) And there’s much more, from Shakespeare’s money-obsessed Shylock (who was portrayed until Victorian times as an abject red-haired devil) and Dickens’s child-exploiting Fagin (who also has red hair), to George duMaurier’s sexually predatory Svengali and the skulking Judas of Mel Gibson’s The Passion.

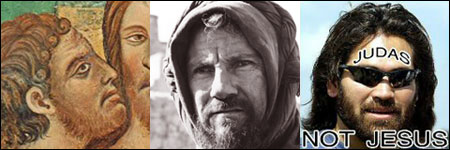

Just as the image of Jesus has morphed over the centuries to reflect the culture’s needs, desires, and fantasies, so has the image of Judas. Contemporary authors have been increasingly sympathetic to Judas. In his 1960 paper “Judas the Beloved Executioner,” psychoanalyst S. Tarachov saw the betrayer and Jesus as erotically involved, and a decade later even Broadway, in Jesus Christ Superstar, portrayed a sympathetic, activist, countercultural Judas who felt he was helping Jesus’s political opposition to Rome. By 1988, Martin Scorsese, in The Last Temptation of Christ, gives us Harvey Keitel’s Judas not as an arch-Jewish antichrist but as the ultimate antihero who was simply, and unhappily, following Jesus’s wish to be betrayed. Today, more than ever, traditional Christianity and beliefs are undergoing tremendous change. Doubts and revisions are now culturally celebrated — thus the extraordinary popularity of The DaVinci Code

— and the intense public interest in the Judas gospel is just one more example. Every culture gets the Judas it needs and imagines, and the Judas of this newly discovered gospel is not just kinder and gentler, but a theological and cultural hero.