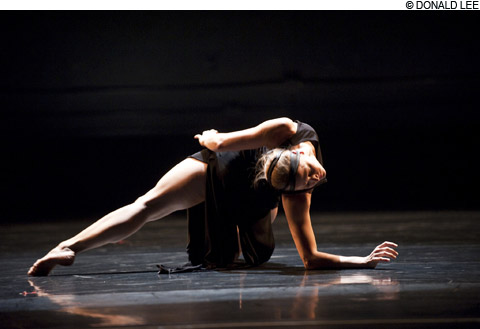

NEW-CIRCUS? Azure Barton’s dancers can slide from classical extensions to rubbery falls to gestures of appeal or insult. |

November brought a dense cluster of dance events to galvanize our thinking about how dancers have re-imagined their craft and challenged their audiences over the past few decades. Fortunately, a bunch of examples will be on view till mid-January at the Institute of Contemporary Art. The ICA's big "Dance/Draw" show aims to "trace the journey of the line" from page to stage."Dance/Draw" is really two shows. Curator Helen Molesworth has brought the two art practices together without making a very persuasive case for their interconnectedness. I have to say I skimmed over the visual art and sculpture (Greg Cook's review was in the October 18 Phoenix), but I spent a lot of time with the films and performances. Images that actually move before my eyes fascinate me more than fixed artifacts do.

In the galleries there's a generous and thought-provoking collection of films and videos, from the rock-bottom minimalism of Yvonne Rainer's Hand Movie (1966) — five minutes of what one hand can do — to Charles Atlas's searching, sometimes hilarious, multi-layered survey of a career, Rainer Variations (2002).

The stunning three-dimensional dance film After Ghostcatching (2010) conjures up a world where the act of dancing produces its own graphic image in time and space, although hardly anything in the film resembles a dancing person. In 1999 the members of the OpenEnded Group (Marc Downie, Shelley Eshkar, and Paul Kaiser) filmed Bill T. Jones with motion-capture technology for the first Ghostcatching. Now they've re-sampled Jones's image and his voice, creating new trace forms that stiffen into spiky figures, loop into spirals and knots, morph for a few seconds into the skeletons of prehistoric lizards, and finally rocket off into distant galaxies.

William Forsythe lays out imaginary lines and circles to use as permeable boundaries in chapters from his educational video Lectures from Improvisation Technologies (2011). The choreographer engagingly demonstrates how you can activate parts of your body to move in ways you never suspected, by wiggling through the memory of your perfect port de bras, or clambering around the axis between your extended right finger and the floor.

BODY ART Tseng Kwong Chi’s Bill T. Jones Body Painting with Keith Haring is part of “Dance/Draw” at the ICA. |

Apart from these two examples, most of the ICA's dance entries didn't seem to have much to do with drawing, and they leaned heavily on the postmodern experiments of half a century ago. One misconception about the watershed '60s is that dance reduced itself to everyday movement. Although dance technique was abolished for a while, even the earliest experimenters were adapting and extending vernacular moves so they didn't look ordinary at all. Everyday movement was the first option after the upstarts had stripped away the conventions and pretensions of dance as we knew it. They danced on from there. Only a handful of people developed the austere possibilities of a danced minimalism. In Lucinda Childs's Calico Mingling (1973), four dancers walk in precise, interwoven patterns on an outdoor plaza with geometric tile designs. Shot from overhead by Babette Mangolte and projected on a gallery wall, it's a great example of dance minimalism's mesmerizing power.The notion of "the everyday" must have prompted the ICA's inclusion of Jérôme Bel's performance piece Cédric Andrieux and his film Véronique Doisneau (2005). Bel is a French conceptual artist with a big intellectual cachet in the dance world. He doesn't seem to dance himself, or choreograph. For the series represented at the ICA, he directs dancers in lecture-demonstrations where they talk about their careers and dance some of their favorite passages. These are political statements, not personality profiles. Bel says in the program note that he means to "analyze the extent to which a particular artistic project or a particular style alienates or emancipates an artiste either as a historical subject, a member of society or as a worker." Dancers work hard. They get exploited. They obsess over how their bodies look in the mirror.