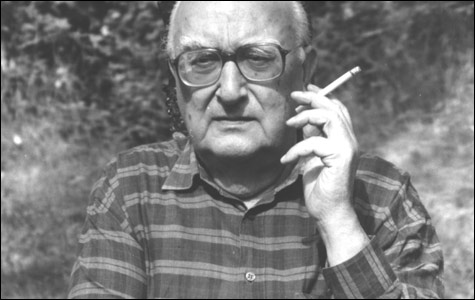

BAD SHAPE: If Camilleri’s Inspector Montalbano can’t get out of bed in the morning, what hope is there for the rest of us? |

| The Wings of the Sphinx | By Andrea Camilleri | Translated from the Italian by Stephen Sartarelli | Penguin | 240 pages | $14 [paper] |

One of the attractions of our getting hooked on a series of novels with a recurring protagonist is the reassurance that once every year or so we'll have a friend to catch up with. What we don't like to think about is how it'll feel when that friend is in bad shape.The Wings of the Sphinx is the 11th of Andrea Camilleri's Inspector Montalbano novels. (The next four in the series await what falls on the ear of this non-Italian-speaking reader as Stephen Sartarelli's graceful translating.) In this one, Montalbano's state of mind goes beyond his usual benevolent crankiness. Neither a tyrant nor a pushover, he's dogged, intolerant of fools, devoted (in spirit, at least) to long-distance girlfriend Livia, a man who approaches a meal as Casanova approached a woman — that is, with the finesse of those who are able to savor as they satisfy their hunger. He's one of the most grounded characters in contemporary popular fiction.

So to open The Wings of the Sphinx and read on the first page that "nowadays early mornings very often inspired a feeling of refusal in him, a sort of instinctive rejection of what awaited him once he was forced to accept the new day, even if there were no particular hassles awaiting him in the hours ahead" is to be thrown immediately off guard. If Montalbano can't get out of bed in the morning, what hope is there for the rest of us?

Part of the pleasure of these books, which are set in an imaginary Sicilian town, is the deep appreciation of life they convey. (Although they're very different in tone, you could say the same of the late Magdalen Nabb's Marshal Guarnaccia volumes, which are set in Florence.) Camilleri is not the crime writer to pick up for hard-boiled mayhem. The Montalbano books are procedurals, most of them resolved with little additional bloodshed. As with a lot of series books, the appeal for long-time readers is in being once again in company you like.

The mystery here concerns a young woman found dead whose only identifying feature is a sphinx-moth tattoo on her back. Soon Montalbano hears about two young women with identical tattoos who have vanished. It's not giving away much to say that the solution has something to do with the sex trade. But this is where Camilleri's becalmed perspective comes in. The ugliness of human trafficking has inspired rescue fantasies in novelists and journalists alike. Camilleri doesn't editorialize.

What's more important in The Wings of the Sphinx is its portrait of a man with innate equilibrium suddenly finding that the ground beneath his feet has turned to choppy seas. As a mystery, the novel is a deftly executed entertainment. As a portrait of the particular uncertainties of middle age, it's subtle and very moving. The emphasis on mood, on the nuances of human exchange, on the sudden perceptions where you see yourself clearly if not as you'd like to be seen — all of this might be at home in those accomplished novels of manners that English female writers have so long been good at. Like their efforts, The Wings of the Sphinx offers human-scaled satisfaction, the kind you get from an observer who knows the precise balance between shrewdness and compassion. If there's such a thing as a rueful entertainer, Camilleri is one.