MISERY: A Wayuu child shows clear signs of severe malnutrition, including reddish hair, distended belly, and spindly arms and legs.

|

Postcards from the edge

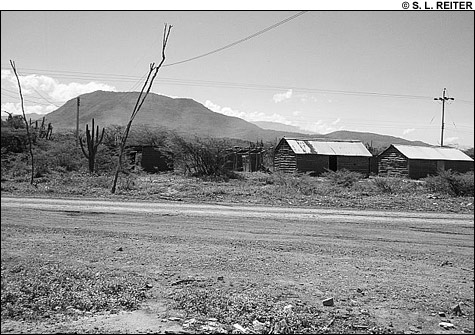

If you follow the road out from Albania, you come to more tiny settlements with picturesque names: Chancleta, Patilla, Roche, Tamaquito. But the villages are anything but picturesque. If Albania offers at least a veneer of activity and life, these villages, according to one union leader from the mine, belong to the “living dead.” Barefoot children with distended bellies cough or lie listlessly. While an American visitor watches, a toddler coughs up a parasitic roundworm. Gaunt adults sit in scarce patches of shade among wattle-and-daub huts. Oil barrels with MOBIL stamped on the side collect sparse rain water, left over from the days when Exxon-Mobil owned the mine. (In 2002 Exxon sold its operation to the current owners, a consortium of multinationals, three of the largest mining companies in the world: BHP Billiton, based in Australia; Anglo-American, a British-South African company; and Glencore/Xstrata, in Switzerland.)

Although the coal from this region powers electricity here in Massachusetts, as well as much of the rest of the US and Canadian Eastern Seaboard, Europe, Israel, and Japan, Colombians see the coal only in the displacements, the contaminated air, and the scars on their land. The indigenous Wayuu village of Tamaquito has no electricity, nor health services, running water, or schools. It is surrounded by fertile farmland, where community members used to plant their own crops and find work on surrounding ranches. Tamaquito’s children used to attend primary school in Tabaco. Now the company has bought all of the farmland, leaving the village an isolated island.

“Tamaquito is a very, very poor indigenous community,” explains Jairo Dionisio Fuentes Epiayu, the native governor. (Tamaquito is governed by traditionally elected authorities.) “We are suffering a lot here because the mine has completely surrounded us. We don’t have access to the roads to move or leave our village. We have to walk on trails, and it takes four or five hours to get to Patilla [the nearest village]. This means we don’t have access to anything. Cerrejón won’t even let us on its property to hunt. We used to support ourselves by hunting, by planting, but now that Cerrejón has bought up everything around it, we have no way of surviving.”

Cerrejón’s slogan is “Coal for the world, progress for Colombia.” It’s repeated on the company’s Web site, in its advertisements, and on billboards ubiquitous in the province. Eder Arregocés, a community leader from Chancleta, takes an ironic view of these oft-repeated words. “If that is so, I’d like to know, to what country do the towns of Chancleta, Roche, and Tabaco belong? There are droves of young people just wandering around because there is no school, there is no work. It may be one of the largest coal mines in Latin America, but most families here eat one meal a day.”

“At first we believed what they said, that the mine would bring progress for Colombia,” adds Inés Arregocés, another villager displaced from Tabaco. “But now we see that it’s sadness and destruction for Colombia, because we were displaced from our homes, from our lands. . . . They are dumping huge piles of earth where our houses, our streets, our schools used to be. And now it’s just giant mountains of dirt, contamination, and suffering for us.”

“We’ve gone from being a productive community,” adds Wilman Palmezano of Chancleta, “to a community of paupers.”

MOUNTAIN OF WASTE An unobstructed view from the village of Patilla of the Cerrejón mine’s “overburden,” or rock and soil waste.

|

Silver and coal

Although the mine’s impact on local communities has been devastating, some people inside Colombia and outside are reaping benefits from the operation. The most obvious beneficiaries are the management-level employees of the mine itself. Many of them live in the town of Mushaisa, inside the gated compound of the mine. There they enjoy a quiet suburban lifestyle that seems light-years removed from the villages outside. Paved, well-lit streets are flanked by green lawns and brightly painted houses. Tennis courts, swimming pools, movie theaters, and shops provide entertainment and supplies. Electricity flows everywhere, and water runs sparkly clean from the taps. Children attend one of the country’s best bilingual schools, where they follow a US curriculum. Outside, the illiteracy rate is 65 percent and most children don’t make it past the fifth grade — if they attend school at all.

Most of the mine’s 5000 direct employees and 5000 subcontracted workers also benefit from the mine’s presence. The majority of the direct employees have a significant level of technical training, and work operating heavy machinery or in the machine repair shops. They don’t live in Mushaisa — that’s reserved for high-level management. But neither do they live in the impoverished villages around the mine. Most of them come from cities like Barranquilla and Valledupar, where they had access to higher education.