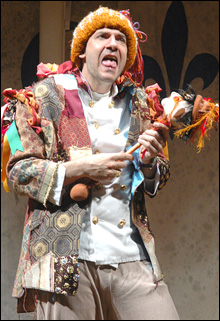

Shakespeare might have subtitled All’s Well That Ends Well (presented by Actors’ Shakespeare Project at Cambridge Family YMCA Theater through May 14) Smart Women, Foolish Choices. The rarely produced play does not present a problem in the broad societal way that The Merchant of Venice and The Taming of the Shrew do. The difficulty here is more specific: the not unperceptive heroine spends the entire play doggedly pursuing a guy who’s not worth the chase. As critic Harold Bloom opines of the snobbish cad on whom orphaned healer Helena has set her stubborn heart: “Bertram has no saving qualities; to call him a spoiled brat is not anachronistic.” In Benjamin Evett’s production, which is mounted as if folks were putting on a show, with on-stage trunks in which to rummage for costumes, Bertram is played against type by comic marvel John Kuntz. (He doubles as Lavatch the Clown, who also has an impregnate-’em-and-leave-’em way with women.) Kuntz’s Bertram is less callow and dashing than callow, posturing, and immature. We are left to hope he will grow out of his awfulness.

Shakespeare might have subtitled All’s Well That Ends Well (presented by Actors’ Shakespeare Project at Cambridge Family YMCA Theater through May 14) Smart Women, Foolish Choices. The rarely produced play does not present a problem in the broad societal way that The Merchant of Venice and The Taming of the Shrew do. The difficulty here is more specific: the not unperceptive heroine spends the entire play doggedly pursuing a guy who’s not worth the chase. As critic Harold Bloom opines of the snobbish cad on whom orphaned healer Helena has set her stubborn heart: “Bertram has no saving qualities; to call him a spoiled brat is not anachronistic.” In Benjamin Evett’s production, which is mounted as if folks were putting on a show, with on-stage trunks in which to rummage for costumes, Bertram is played against type by comic marvel John Kuntz. (He doubles as Lavatch the Clown, who also has an impregnate-’em-and-leave-’em way with women.) Kuntz’s Bertram is less callow and dashing than callow, posturing, and immature. We are left to hope he will grow out of his awfulness.

All’s Well is an interesting if odd duck in the Shakespeare canon. (Scholars speculate that’s because the First Folio version is based on a rough draft.) Raised in the home of the Countess of Rossillion, Helena is a commoner, the daughter of a famous physician who left her some of his remedies. As it happens, one of these might cure the dying King of France of a “fistula.” It works, and she asks as reward the hand of the Countess’s son, who has no choice but to comply. Before consummating the marriage, however, Bertram flees to the Tuscan wars to pursue gallantry and girls, swearing not to return home until Helena’s no longer part of the scenery. To her he sends a rude letter promising to shun her until she can get from him his ancestral ring and a bun in the oven. In other words, until the 12th of Never. Undaunted, Helena pursues him to Florence, conscripting female compatriots to aid her in fulfilling the requirements. As in Measure for Measure, this involves the “bed trick,” in which the lawful wife is substituted in the dark for Bert’s lust object du jour.

At ASP, the dark side of the comedy is underscored by mournful madrigals and folk songs of spurned love. Meanwhile, rough slapstick intrudes on the play itself, with Three Stooges–like comedy applied not just to the Malvolio-like subplot in which Bertram’s boastful coward of a sidekick, Parolles, is duped and exposed but also to the main plot, which finds the regal Countess of Rossillion (played by Paula Plum with a cunning charm that defies the term “dowager”) submitting to little titty grabs and thwacking sessions with the Clown, in which role Kuntz strives valiantly to be amusing despite the relentless unfunniness of the material. (There is much phallic use of bananas in the production, but what the Bard supplies Lavatch is second-banana stuff.)

Jennie Israel is also unusually cast as Helena, but she brings a sharp serenity to the righteous stalker. Allyn Burrows is deliciously dejected as found-out military popinjay Parolles — who with exposure turns from trimmed-down Falstaff into Poor Tom. Ellen Adair is a lovely Diana (the Florentine woman Bertram thinks he seduces), and Bobbie Steinbach, in the dual roles of no-moss-on-me elderly lord Lafew and Diana’s mother, proves again that she has the best comic timing in Boston. The songs, when rendered by the better singers, lend a piquant counterpoint to the banana peels.

The human mind is as unfathomable as the human heart, and some of the voyages charted by famed neurologist Oliver Sacks are as fantastical as those of Pericles. As theatrical, too, it would seem. Sacks’s Awakenings was the basis for both Harold Pinter’s A Kind of Alaska and an Oscar-nominated film. Then in 1994, director Peter Brook and his writer collaborator, Marie-Hélène Estienne, created the “theatrical research” The Man Who, which Nora Theatre Company is giving its New England premiere (at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre through May 7), from Sacks’s 1985 The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. A victim of visual agnosia, that man-who is represented, along with 16 other brain-injured individuals, in this at once clinical and mysterious theater piece that conjures the territory between imagination and neurological disorder and quietly catalogues the courage it takes to live there.