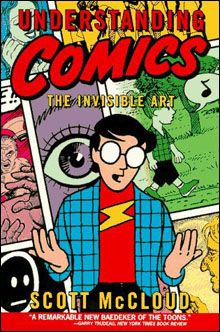

Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics |

Scott McCloud writes about cartoons in a comic book format, and has become one of the world’s premiere comics theorists. In his books, he draws himself as a professorial narrator who invites the reader onto the page to check out his ideas about cartoon history and the psychology of what happens when we read comics.His first book about cartoons, Understanding Comics, was published in 1993 and was promptly added to the syllabus of every cool college professor across the country. Seven years later he drew Reinventing Comics. It was a visionary book, but by his own admission it was also too ambitious: a vessel for every theory he’d ever had about cartoons, Reinventing became an intellectually bloated history manual and was greeted with mixed reviews.

This fall McCloud will publish a new book, Making Comics. He’s a kind-hearted and fascinating guy, and our interview quickly spiraled into a three-hour love fest. Here are a few excerpts.

What’s hard for you to draw?

There are a few things cartoonists will tell you are just plain hard to draw. Bicycles are hard to draw. You really need to look at a bicycle in order to draw a bicycle. You think you know what it looks like, alright? Until you actually sit down to draw it, then you totally – you completely choke on it.

All those gears and everything!

Yeah, it’s the gears and also the struts don’t really follow any logical pattern that you can remember. So you just have to look. But these days with Google’s image search you can — you just find out what anything looks like. It doesn’t matter. In the old days when I was starting out in the ’80s, everybody had their collection of National Geographics and we would go out and buy all these stupid magazines and you know cut out picture and think, “Oh there’s a koala bear — I might have to draw a koala bear someday!” And you know you’re never ever going to have to draw a koala bear and you’re just wasting your time with your scissors and your eight-and-a-half by 11 paper and your glue sticks sticking these things down and spending hours –

You’re just avoiding work!

Yeah, just avoiding – right! Avoiding work. I actually love drawing what my peers dismissively call “backgrounds” but what I like to call environments. Just sidewalks and cityscapes and skies. Fields of grass and everything. Or “the rest the world” is another way I like to refer to it. Because one of the problems with a lot of comics art today is that many comics artists learn how to draw people and they just stop there. And they become what Will Eisner called “slaves to the close-up.” They try to close in on the characters as much as possible because they know if they keep their camera angles tight they can keep their backgrounds down to a few lines. I think the European tradition is much more conscientious about drawing the full range of subjects. And that’s why I think there’s a very rich tradition of comics and of world building in European comics. I think that’s something we could learn from.

Do you think that’s because American culture is so celebrity and persona driven?

I don’t know. Possibly yes. In fact I found it easy to identify the “house style” of European comics and the “house style” of Japanese comics. If I was living in Japan what would I look at in American comics and think, “Oh yeah, it’s an American comic — you can tell because they’re all doing this”? What would be that constant element? And I think it might be the primacy of the figure if you have the figure sort of playing to the audience. And that might actually have its roots in the origin of comics in America: really a kind of paper vaudeville.

Comics evolved out of stage plays, out of the idea that you’re sitting in the front row of the audience and they’re performing in these little vaudeville boxes just for you. Characters in American comics are more likely to face out. I thought that was interesting when I started. We face the audience more in American comics than characters do in Japanese and European comics. You don’t really follow characters into their world the way you do in other cultures here in America. Here in America characters tend to block you at the door. They’re in the center of the panel. They fill the panel and they face you. You can’t get into their world. You know? Spiderman’s always there, always facing you. Even when he’s facing the villain he makes sure you can see all of his pecs and his trapezius muscles and his, you know — you can see that Spidey’s there to please you! Spiderman’s there to entertain you. And I’m thinking, “You know what? Maybe it’s time to get beyond this.” It’s been a hundred years, people!