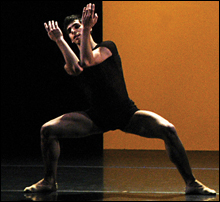

COMPAÑÍA NACIONAL DE DANZA 2: Duato’s Remansos was playful and maybe more. |

There were baby ballerinas on screen and on stage for the first full weekend of Jacob’s Pillow 2006. In its smaller Doris Duke Studio Theatre, the Pillow offered Ballets Russes, the 2004 documentary from Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine that was shown at the Kendall Square Cinema and the Museum of Fine Arts last year. Spanning the decades from 1930 to 1960, it details the rise and fall of the two Ballet Russe companies that emerged in the wake of Serge Diaghilev’s death in 1929, starting with the trio of very young — ages 12 to 14 — Russian émigrée girls whom George Balanchine found in Paris in 1931 and chose to be the stars of the new Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo. In the Ted Shawn Theatre, the spotlight was on the 14 16-to-21-year-olds of Spain’s Compañía Nacional de Danza 2, which was making its third Pillow appearance in four years.CND2 is itself a baby, having been formed in 1999 by CND director Nacho Duato and his assistant, Tony Fabre, who together provide most of the repertoire. The dancers receive two-year contracts and can promoted into the first company if they’re good enough and there’s room. Their opener this time around, Duato’s Remansos, was set on a trio of American Ballet Theatre men in 1997 as Remanso, to music by Enrique Granados; it’s included in the 1998 DVD American Ballet Theatre Now: Variety and Virtuosity. Duato has since expanded the piece to include three preliminary sections in which three women dance with the three men.

The program informed us that the dance had been “inspired by Granados’ music and by the world of poet Federico García Lorca.” The Catalan composer Granados died in 1916, at age 48, after the ship in which he and his wife were traveling was struck by a German torpedo and he jumped into the ocean to try to save her. “Remansos” — “backwaters” — is the title of a suite of five poems from García Lorca’s 1922 volume Primeras canciones. The first, “Remanso,” reads,

Cypress.

(stagnant water.)

Poplar.

(crystalline water.)

Willow.

(deep water.)

Heart.

(tears.)

The dance itself is set before a low square white wall that in the final section is colored by the lighting: lavender, lime, ocher, sky. Centerstage front stands a single red rose. The first three sections — “Danza Oriental,” “Minueto,” “Danza Villanesca” — are male-female duets, athletic, contests almost. The end of “Danza Villanesca” finds the women kneeling in a row; one picks up the rose and sticks it against the wall as the women retire. In the final, original section, to Granados’ pleasant but unprepossessing “Valses poéticos,” the men reappear, more playful and intimate now that they’re alone, climbing the wall, peering goofily over it, dancing in solos and duets. Remansos climaxes with the third man — Jonatan de Luis Mazagatos substituting for the injured Jon Vallejo in the Pillow performances — hanging upside down from the wall, the rose between his teeth. But the disappearance of the women betrays the work’s seam. Are the men García Lorca’s trees? His waters? His recurrent half-moons?

Tony Fabre’s 2005 Violon d’Ingres gets its name from a 1924 Man Ray image of Kiki seen nude from behind with a cello’s sound holes in her back: woman as instrument on which man plays. Fabre says he took his inspiration “from some compositions for string by Paganini, Bach, Vivaldi, imagining the bodies of the dancers as the strings of a violin, a cello, a viola.” His string orchestra is tuning up as the curtain rises to find the dancers writhing on a bench. The jagged idea that Rachmaninov used for his Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini dominates the early going, which is marked by the usual couplings and uncouplings and a whimsical bit of voyeurism (a woman hiding under the bench and watching). Grieg, Fabre’s father’s favorite composer (on its previous visit, in 2004, CND2 danced Fabre’s Aus Holbergs Zeit), contributes Anitra’s Dance from his incidental music for Peer Gynt; Kenji Matsuyama becomes an on-stage triangle player, complete with music stand, but at the end of the section he goes triangle crazy and they have to take it away from him. Violon d’Ingres ends as it began, writhing and tuning up. Like Remansos, it’s playful, light, perhaps not as light as it looks.

Duato’s 1990 Rassemblement is a political number in the vein of his Na floresta (rain forests) and Coming Together (Attica); here the subject is human rights in Haiti. The music is Toto Bissainthe’s Rasanbleman; the costumes are the country-peasant clothes of Duato’s Jardí tancat and Arenal rather than the dancewear of Remansos and Violon d’Ingres. The focal figure, Jonatan de Luis Mazagatos, goes to sleep amid the dancing, and when he wakes up, he shows the wary instinct of a hunted animal. To no avail, it would seem, since two men in black appear to torture and murder him, but the rassemblement of the community suffices to resurrect him, after which the stirring call of “Liberté” rings out.