Seeing Mark Morris Dance Group do his L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato here in Boston back on January 20 and then New York City Ballet perform George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco and Symphony in C the following evening in New York was a reminder that the two 20th-century choreographers most noted for their use of music couldn’t be more different. Morris celebrates; Balanchine strives. Morris is loose and floppy, Balanchine disciplined and precise. Balanchine choreographs for adults, or sometimes angels; Morris choreographs for children, or rather for the inner child in us all.

Seeing Mark Morris Dance Group do his L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato here in Boston back on January 20 and then New York City Ballet perform George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco and Symphony in C the following evening in New York was a reminder that the two 20th-century choreographers most noted for their use of music couldn’t be more different. Morris celebrates; Balanchine strives. Morris is loose and floppy, Balanchine disciplined and precise. Balanchine choreographs for adults, or sometimes angels; Morris choreographs for children, or rather for the inner child in us all.

L’Allegro is an odd duck of a dance, descended from Milton’s 1630ish poem pair “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso” by way of the 1740 Handel oratorio that interwove their verses and added at the end a reconciling “Moderato” section set to a text by Charles Jennens. Morris does just the “Allegro/Penseroso” part with two numbers from Handel’s “Moderato” thrown in; he could as easily have omitted them and called his dance L’Allegro ed il Penseroso . Still, as Debra Cash noted in a WBUR arts blog last week, American critics have been canonizing this paean to the human spirit since its 1988 Brussels premiere. “The piece pours forth treasures,” Arlene Croce summed up. Joan Acocella spoke of the finale as bringing us to “a realm of rapture that recalls Dante and Joyce.”

Always emphasized is Morris’s incredible variety of movement. That would include running, jumping, hopping, kicking, bowing, swiveling, turning and reverse-turning, rolling, sliding, going to ground, and running off stage in different directions, in unison and in canon, on the beat and off, upstage and down. It’s the kind of movement that makes audiences think they could get up on stage and do it themselves; it conjures children’s games and the jubilant dances of the Peanuts gang. It’s anonymous, communal movement for boys and tomboys; the girls, former Phoenix dance critic Laura Jacobs has written in the New Criterion , remind her of Anybodys in West Side Story . There’s no meanness, no darkness, no individuality, not even the kind you see in a communal dance like Twyla Tharp’s The One Hundreds .

L’Allegro is a high-class illustration of Milton’s two poems: the Graces, the pensive nun, the sweet bird, the hunting hounds, the cricket on the hearth all come to vivid life. Even when setting classical music with no text, like Bach’s C-major Cello Suite, Morris tends to be literal; in Barbara Willis Sweete’s film of the making of Falling Down Stairs , you can see him choreographing with the score on his lap. Balanchine doesn’t illustrate, he translates. It’s not that the movement in Concerto Barocco doesn’t “listen” to the score of Bach’s Double Violin Concerto, but where Morris is predictable, Balanchine is surprising, even quirky. The two ballerina soloists in Concerto Barocco represent the solo violins sometimes but not always; there’s no musical equivalent for the male soloist in the second movement, or for the way he disappears and the second woman soloist comes on briefly (to warn the first?).

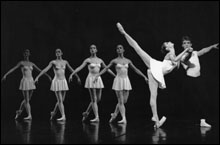

Morris gives us comfort-food dance; Balanchine is Jacob wrestling with the angel. Nancy Reynolds in Repertory in Review describes Concerto Barocco as “a ballet especially for the legs and feet.” Balanchine is all about legs and feet, about limbs and appendages galvanized by the center of the body and reaching, reaching, reaching. The original version of his Square Dance , another dance set to Baroque music (Vivaldi and Corelli), has Elisha Keeler calling, “Now keep your eye on Pat [Patricia Neary]/See what she is at/Watch her feet go wickety-wack.” MMDG feet never go wickety-wack; they don’t do much of anything.

In the Balanchine Library video essay on “Attitude,” Merrill Ashley demonstrates a back-attitude position from the slow movement of Concerto Barocco, the free leg bent at a 90-degree angle, knee lifted to hip level, back straight. It’s neither natural nor easy, the human body stretched into an ideal vision of itself. And when Jeffrey Edwards turns her in that position, with Gordon Boelzner at the piano, in a 30-second excerpt, I wouldn’t trade it for all of L’Allegro.