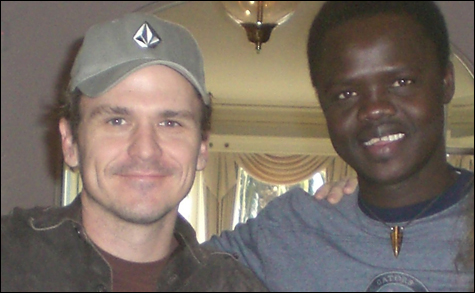

Dave Eggers and Achak Deng |

If Dave Eggers’s career is any indication, the best way to become a writer of importance is to convince everyone you’re a self-indulgent jerk and then pull the rug out from under them.

Eggers shook the literary establishment with the release of his 2000 debut, the Pulitzer Prize-nominated memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, which chronicled the period between the sudden deaths of his parents, his adoption of his young brother, and his attempts to make a name for himself in San Francisco’s literary scene.

The book is the work of a merry prankster with an ax to grind, with its thirty pages of trickster introductory remarks, long imaginary tirades against the author’s potential enemies, and a fake transcript of Eggers’s interview for MTV’s The Real World juxtaposed with lots of genuine and wrenching prose. Eggers became known as an unpredictable self-promoter, hosting elaborate public readings while simultaneously becoming hostile and confrontational toward journalists. Regardless of what you thought of him, it was exciting to see an author matter again.

The over-riding quality that made Eggers such an intriguing and maddening figure, both in his published work and his public persona, was the impenetrability of the author’s identity. Was he the nervous-but-playful surrogate father to his orphaned brother, the reclusive and angry foe of anyone who questioned his actions, or the performance artist looking to break down any wall he could?

The answer — which largely separates his fans from his critics — is that he was all of these things. Yes, AHWOSG is self-absorbed and emotionally juvenile in many instances, and its post-modern impulses are often tough to stomach. Eggers was so aware of when his indulgences would become excessive that he confronted the reader with them in the text — a critic-proofing of his work that critics deemed desperate — and dared you to like him anyway. Eggers’s naysayers seized on this, chastising him for a lack of editorial discipline and accusing him of just wanting pity and attention. His fans saw things differently, arguing that the book was necessarily moody and inconsistent. So was he. So was his audience.

Reconstruction

Being willfully divisive isn’t the best way for a talented writer to establish a career, and the steady decline in publicity and sales surrounding Eggers’s next release, 2002’s You Shall Know Our Velocity!, was probably a consequence of that. Treading emotionally volatile terrain similar to AHWOSG but tempered by its structure as a more conventional novel, the book offered readers something its predecessor refused: growth and resolution, weightier than fleeting catharsis. Its relative lack of success was probably due to its transitional tone; it was similarly erratic and compelling, but less interested in affronting the conventions of the novel.

Eggers’s writing has continued to mature. As he’s grown older, gotten married, and had a kid, his output and his public image have become more sober and earnest, though his writing no less vivid or fluid. Instead of applying his naturally self-questioning mindset to characters too much like himself, he has steadily broadened his palette, creating characters with singular and diverse concerns. In 2004’s short story collection How We Are Hungry, Eggers deftly portrayed a man doing home-improvements to save his floundering marriage; a woman encountering poverty, racism, and class privilege while climbing Mount Kilimanjaro; and a dog who just loves to run. Even in instances when the author’s perspective still seemed transparent, it was this way in measure, favoring coherent characters and plot structure over a need to say everything he had to say all the time.

The increased generosity of Eggers’s worldview has been matched by his backstage efforts as an editor and philanthropist. He is the co-founder of McSweeney’s, the San Francisco publishing house best known for its humorous online journal and its quarterly literary journal, which has evolved from a scrappy collection of ambitious stories into a diverse and immaculately designed outlet for young writers. One recent issue was devoted to Icelandic writers and contained a pullout from one of the country’s gossip rags; another came packaged in a cigar box. The monthly magazine The Believer, also published by McSweeney’s, has found a niche with young writers and readers thanks to its diverse interviews and commentary, all tangentially falling under the realm of literary criticism.