SCOURGE: Dancing, singing, drumming, and talking. |

New ballets must be one of the world’s most expensive consumable products. Choreographers keep hustling up new ways of moving and arranging bodies to serve this market, but what’s new isn’t necessarily contemporary, and what’s contemporary doesn’t necessarily reflect anything about life today.

Last week’s performances brought up the riddle of how dance communicates — as distinct from how it looks. Nacho Duato’s Compañía Nacional de Danza 2, from Madrid, seems to think of itself as up-to-date, but for its two Boston performances it offered a three-part remix of Ailey-constructivist-fusion dancing with serious but invisible themes. Across the street, Boston Ballet’s “New Visions” program showed that the classical tradition hasn’t lost its power to speak.

Sponsored by Celebrity Series at the Shubert Theatre, Compañía Nacional de Danza 2 reprised works it’s shown at Jacob’s Pillow, all choreographed in the 1990s by Duato. Director of both CND2 and the main Compañía Nacional de Danza, Nacho Duato has gained a big reputation in Europe as a guest choreographer. His training began in the 1970s at the Ballet Rambert School, after that company had transitioned into modern dance, and he continued his studies with Maurice Béjart’s Mudra school and the Ailey school in New York. He’s among the best-known of the generation of European contemporary dancemakers now in mid career.

Gradually since the 1960s a lot of theater dance has taken on an almost ideological resistance to identifying itself with either modern dance or ballet. At the same time, it relies heavily on both supposedly outmoded genres to supply the movement vocabulary. The Duato dances seen in Boston exemplified the clean, uncontroversial, eclectic gloss of “contemporary dance.” I realized that one reason all three dances looked alike despite their thematic differences was that they had no physical point of view, only a determination to make the body move in unusual, preferably thrilling ways.

Remansos, to piano pieces by Enrique Granados, was mostly angular, quirky duets and trios, with the women manipulated into crotchy, upside-down lifts, and with assorted novel shapes, leaps, bends, and pirouettes strewn into the fast-paced comings and goings. It seemed as if there were a jutting limb, a wiggling shoulder, a wide step, or some other embellishment for every note and frill of the music.

Halfway through, there was some dramatic business with a red rose that had been implanted in the floor downstage center as the ballet began and ignored by the dancers until that moment. The insertion of a prop into an otherwise propless, plotless ballet guarantees drama of some kind, or at least mystery.

A woman snatched the rose. She may have handed it off to one of the other dancers, but eventually a woman in possession of the flower crept behind a large white panel, her arm slinking after her, until the rose coyly disappeared. The only significance to this that I could tell was that it introduced a new part of the dance featuring three men in successive solos and groupings. But the overall drive to keep moving and creating new and remarkable gyrations didn’t change.

Coming Together is set to an imposing post-minimalist score by Frederic Rzewski. I couldn’t tell why there were several sets of costumes and footwear in this piece, or why two dancers brought spotlights onto the stage and shone them onto two other dancers, or why a curtain rose to reveal backstage paraphernalia just as the dance was coming to an end. Rzewski’s score included a loud voice reciting a text two or three words at a time, but the orchestration often drowned him out so you might not have been meant to follow his drift.

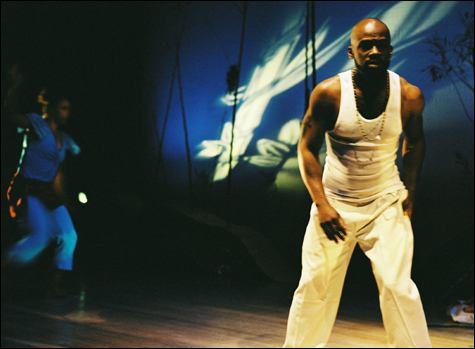

The program notes for Coming Together, and for the following work, Rassemblement, told of urban dynamics and human rights. Set to some Haitian folk songs arranged by Toto Bissainthe, Rassemblement apparently concerned slavery and liberation and voodoo in Haiti. It wasn’t any more specifically expressive than the other two dances.

Brake the Eyes, Jorma Elo’s new piece for Boston Ballet, also applied sensational effects against otherwise formal movement patterns. Elo is another compulsive inventor of movement, but in this work, and in the two other ballets on the program, Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia (2001) and Val Caniparoli’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (2004), classical ballet technique was the ground bass or palette from which a rationale or an argument could be proposed. In other words, we didn’t get novelty or diversity for its own sake.

Brake the Eyes is in a way two ballets. A corps of nine dancers create formal but often spectacular displays, patterns for large groups and duets. Larissa Ponomarenko has her own dance, emerging first from the depths of the Wang stage, a tiny, tutu-clad woman with a menacing T-shaped grid of lights looming over her like an airplane taking off. In a silence broken by some groaning chordal sounds, she dances a progression of balletic postures and dislocations. She glances at herself, at the near-space around her, as if she were checking where she is or what she might try, or judging whether a given move produces the right effect.