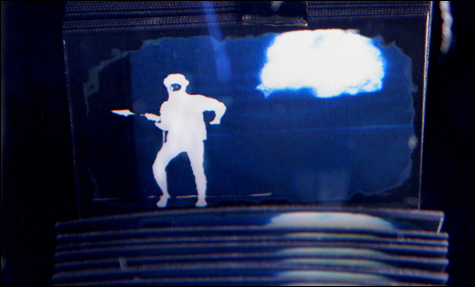

CENOTAPH: Steve Hollinger creates silent dramas. |

Just what is cyberarts? Well you might ask. Is it art that draws on the latest technological advances in software-driven interactive imagery? Yes. Is it art that reconnects with primitive mechanics like those reminiscent of 19th-century circus sideshows? That too. Could it be digitally manipulated film stills enlarged to the size of hotel windows? You guessed. Now in its eighth year and fifth incarnation, the Boston Cyberarts Festival is a bi-annual spring ritual of diverse performing- and visual-arts events and exhibits hosted by area galleries, museums, theaters, universities, and public spaces. Perhaps cyberarts might best be defined by what it isn’t: it isn’t painting, it isn’t sculpture, and it prefers to move or at least to have moved. Here’s a sampling of this year’s fest.

For those looking to feast their eyes on the cutting edge of technology and art — a dangerously mixed metaphor, I know — a trip to Art Interactive is in order. There, Camille Utterback’s three installations, which visibly consist of two separate and one pair of white movie screens suspended high above even the tallest viewers’ heads, at first look like big abstract paintings. One is made up of multi-colored dots; the others sport all sorts of colorful shapes and daubs, and on the floor below each screen appears a corresponding panel of projected light. Only when you begin to walk on the lighted floor area (whose tiles shift slightly with your steps) do you notice that your movement radically reconfigures the shapes on the screen. Sometimes you’re an inadvertent eraser, wiping away whole networks of design. Other times you’re an inadvertent painter, leaving in the wake of your movements huge swaths of unpredictable imagery. In either case, your motions get picked up by a sensor that translates your body’s activity into a cloud-like force that’s continually re-creating what you see. It’s fun.

There’s no denying the intelligence and the precision of Utterback’s art, or its tongue-in-cheek majesty. Few artists in any medium warrant such scale or offer such variety. A fleeting thought came to me as I watched my moving around leave a new canvas behind: I should have been on drugs. A good hallucinogen hit would have heightened the effects of her shape-shifting projections, and that thought may point to the artist’s achievement but also to her achievement’s limit. For all that Utterback’s art is highly interactive, it is not in the least way personal: one’s own particular shape is not reflected on any of her screens. Instead, every body becomes the same amorphous, rounded force field. Further, the graphic content of her ephemeral creations — the painterly brush strokes, the line drawings, the smears of projected pigment — reflect exclusively the artist’s hand, not the viewer’s. Before her immersion in interactive technology, Utterback made works on canvas that look a lot like her sophisticated etch-a-sketches. For art to be truly interactive, it needs to operate like a conversation: both parties get to set the terms.

ORPHEUS X: Love as hellish agony. |

At the other end of the technological spectrum (with one notable exception) are the contributions to “Picture Show” at the Photographic Resource Center. There, relatively simple mechanical apparatuses — hand-turned gears, solar-powered motors, even an old-fashioned ViewMaster — are enlisted to varying degrees of artistic effect. The press materials for the exhibit describe its five contributors as artists who “engage the idea of the ‘moving picture,’ ” but I’m not sure that’s entirely accurate. Erica von Schilgen, for instance, creates wall-mounted tableaux in which small, flat, metal figurines — a row of miniature arms reaching for a bed of flowers, a grid of antique-looking dolls — are set in motion by a system of cranks and pulleys, sometimes motorized, other times activated by hand. With a color palette reminiscent of Victorian postcards and a style suggestive of children’s-book illustrations, Schilgen’s confections aren’t about moving pictures so much as they are a variant on early mechanized toys.The same can’t be said of Steve Hollinger, who enlists sunlight to animate the psychologically charged images of what amount to motor-driven flipbooks. But not just any motor-driven flipbooks. Encased in weathered, wooden boxes or seen through a glass prism, Hollinger’s cartoons take on the aura of mythical personae, Sisyphus in particular. In Supercollider — imagine a pair of black, square binoculars with two tiny screens where the lenses should be — a man and a woman run toward each other and never meet. In Cenotaph, a hated male figure performs a dance with a sword against a backdrop of a mushroom cloud — all seen through a glass prism mounted on a square of concrete. Combining primitivism with advanced engineering, Hollinger creates silent dramas whose shrunken size is inversely proportionate to their emotional resonance and haunting appeal.

Hans Spinnerman’s unearthly projection of an albino bumblebee the size of a rodent wins the Houdini prize for its technological prowess and mysteriousness. Encased in an elaborate bell jar that looks as if it had come from a Jules Verne novel, Spinnerman’s bee hovers silently in pitch-black space, and no matter where you stand in relation to it, it’s always flying toward you.