MINIMUM MISHEGAS: But Murakami’s knack for making the everyday exotic, and the elusive tangible, is as sharp as ever. |

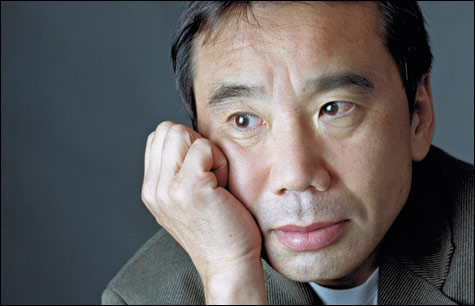

The typical Haruki Murakami protagonist is torn between women who are unattainably gorgeous — often suicidal — and those who are just unbelievably cute — often young and unfinished. Both the guy and the dolls are present in his new short novel, After Dark, but there’s a twist: it’s the two women who are the protagonists and the man who’s the tertiary figure.

This might not sound like a big deal, but given how closely Murakami’s guys follow the same script, albeit in ever-fascinating variations, it’s refreshing to see him focusing on what women want. Not that he comes up with any startling insights, but the world he creates — of fast-food restaurants and strange hotels, people dying (almost literally) to make connections but able to do so only in fits and starts — continues to be one of the most intoxicating around. His knack for making the everyday exotic, and the elusive tangible, is as sharp as in his "bigger” works, such as The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. No wonder this cult figure is beginning to break out.

The two women here are sisters. Mari is a 19-year-old bookish non-player whose midnight sojourn at a Tokyo Denny’s is interrupted by a jazz musician who was once infatuated with her older sister, Eri. He enlists Mari as a translator when a Chinese prostitute is beaten up in a “love hotel.” It turns out she’s joined the world of the night people because two months earlier Eri — the gorgeous one — decided to go to sleep, waking only to take care of the bare necessities to keep herself alive. Mari can’t get any shuteye with the creepy Sleeping Beauty in the next room, so it’s off to Denny’s.

Murakami keeps the action pretty much fixed on the two women — unusual given his penchant for epic sprawl. Maybe he needed a breather after his previous (and best) novel, Kafka on the Shore. After Dark reads as if he wanted to get the women through their psychic adventures, which take place from just before midnight to just after dawn, with a minimum of Murakami mishegas.

Despite the time frame, the setting of a “love hotel,” and the creepiness of the fourth major character (“the man with no face”), this is no noir meditation. You can tell that Murakami loves genre writing, but he’s too personal and playful to settle for any of the limitations of noir. And too metaphysical — Eri moves intriguingly from one side of a TV screen to another while she’s asleep.

Mari, meanwhile, is subjected to the typical Murakami music list, which runs from Percy Faith to Curtis Fuller and the Pet Shop Boys, as well as to discourses on existence ranging from Godard’s Alphaville (the name of the hotel here) to a bit of Kant. And did I mention the Red Sox? Murakami, it seems, came away with at least a hometown cap from his visiting-lecture stint at Harvard (where his translator, Jay Rubin, is a professor).