SYNÆSTHETES? Before the age of three, we perhaps all “saw” sounds in perfect pitch. |

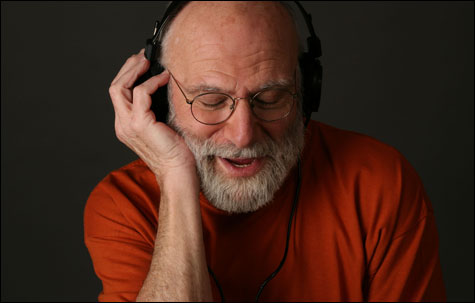

In his New Yorker pieces over the years, Oliver Sacks has shown a talent for setting personal narratives against the increasingly mapped-out maze of human neurology. With Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, he offers further indelible portraits, starting with the 42-year-old doctor with no special talent for music who got zapped by lightning, recovered, became obsessed with Chopin, taught himself to play piano, and changed his life for the better.

Sacks takes a cue from E.O. Wilson’s idea of “biophilia”: just as humans are captivated by things that live, so too do we feel a primordial pull toward music. Per Sacks tradition, Musicophilia illuminates lives of often unimaginable strangeness. If you yourself haven’t been affected by musical hallucinations, it might be hard to fathom being woken at 5 am by “a chorus reminding me that ‘the old gray mare ain’t what she used to be.’ ” Or what it means to “see” the key of G major as yellow, as someone with synæsthesia might.

In the past, such weirdness could call forth the men in white coats, but modern brain imaging proves that such abnormalities have a physiological basis: musical hallucinations correspond with activity in parts of the brain “normally activated in the perception of ‘real’ music.” And synæsthesia — an intermingling of sound and sight, or any two senses — results from “simultaneous activation or coactivation of two or more sensory areas of the cerebral cortex.” There is speculation that infants’ senses aren’t entirely differentiated until they’re about three months old. Until that happens, we’re all synæsthetes.

And all of us may have begun life seeing sounds in perfect pitch. Experiments have shown that about 60 percent of conservatory students who spoke a “tonal” language such as Chinese (in which tone determines meaning) and started musical training between ages four and five had perfect pitch. About 14 percent of US students did. The percentages for both groups went down if students started playing at later ages. Another study concluded that infants recognized perfect pitch far more often than adults and that language development might play a role in inhibiting perfect pitch.

The most haunting character in Musicophilia is British musician Clive Wearing. In 1985, he suffered a brain infection that mostly affected the left frontal and temporal areas. Since then he has been unable to hold a memory beyond a few seconds. From one eye blink to another, Wearing looks out on a new world; if his wife leaves the room for a moment, he panics, thinking she’s been gone for an eternity. Despite his passion for Deborah, he cannot recall her name. But he can remember how to play Bach’s Prelude No. 9 in E — even though he can’t recall having ever played it before. “He remembers almost nothing unless he is actually doing it. . . . ” He also plays the organ, sings, and conducts a choir beautifully — and blissfully.

Sacks writes, “There are clearly many sorts of memory, and emotional memory is one of the deepest and least understood.” Wearing’s most emotionally powerful memories — his passion for his wife and for music — are what sustain him. Without a past or a future, he exists only in the present. Music floods his consciousness, filling each moment like nothing else. “Remembering music, listening to it, or playing it, is entirely in the present.” As is Clive Wearing himself. But you might never forget him, or the many others in this extraordinary book.