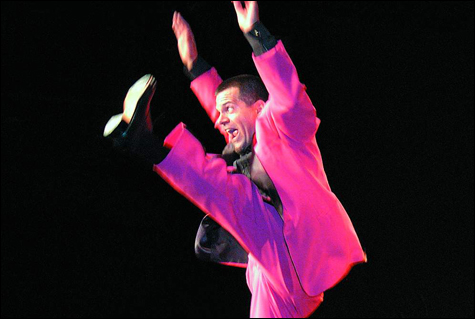

JOSH HILBERMAN: After some modest opening remarks, he became the zany tap wizard he really is. |

Dancers do a lot of talking about their work these days. This can be disarming and engaging as a lead-in to a performance, but it seldom gives away any secrets. Josh Hilberman MC’d his own one-man tap show, Heeling Powers: Rhythms of the Left Brain, last Saturday at the Regent Theatre in Arlington. Except for the loud plaid tuxedo jacket, he looked ordinary when he first came out — 40ish, slightly stocky, with a sparse crewcut. He could have been a businessman or a butcher. But after modest opening remarks, he became the zany tap wizard he really is, dancing in half a dozen styles with costumes of ever-escalating weirdness, mostly in dialogue with the redoubtable Paul Arslanian’s jazz piano.

After a low-key opener with the Barhoppers trio (Hilberman, Little Rose Giovanetti, and Dr. Venus the Tap Dancing Neuropathologist) things swung into gear. Hilberman, now in a turquoise dinner jacket with black lapels, strummed a ukulele and got the audience to whistle “Sweet Georgia Brown” to his tapped obbligato.

Hilberman may be a clown, but he’s no hayseed. In a three-part improvisation on Charlie Parker tunes, riffing with Arslanian in bebop, blues, and mambo moods, he got down to business. With the inventive pleasure of all great tappers, he can throw a complex tornado of steps into the ground, but he can also fling a leg out in space to suspend the beat, or skim bodily across distances without suppressing the rhythmic storm that’s going on in his feet.

Reminiscing between numbers about a lifetime of teachers and fellow hoofers, he acknowledged the distinguished Paul Draper, who combined tap with the step vocabulary of ballet, doing a re-creation of Draper’s Tea for Two. After the grounded Charlie Parker numbers, it was amazing to see Hilberman hurling out leaps, cabrioles, pas de bourrée, and pirouettes, within a cascade of intricate rhythms. He didn’t exactly look balletic, but you’d never have expected the lightness.

He also paid tribute to one of his early mentors, Brenda Bufalino, who was in the audience. After Hilberman had nagged her for a long time, she finally gave him one of her solo dances, Buff’s Bop (1987). “Jo Sterling told me, ‘You wanna sound like Brenda Bufalino? You have to loosen your taps,’ ” Hilberman said, changing his shoes. Buff’s Bop showed off the charged, exuberant Bufalino style.

Besides all this, the evening recapped some Hilberman favorites. In Three Wing Circus (2003), he danced on three big drumheads, sprinting from one to the other as if they were ice floes. In The Warrior (2002), he pounded out body rhythms on a suit of chain mail and a dance belt made of taps. Once in a while, in a fever of barefoot kinetics, he’d slip into a harem girl’s shimmy, but he quickly reverted to his primitive self. To ragtime, he twinkled his newest work, High Heelberman, in two-inch Mary Janes, the classic shoes for a little girl’s dancing class.

At one point, Hilberman explained that the show hadn’t turned out according to plan, because his life had been interrupted by a disastrous flood in his house. Even that gave him fodder for a dance. Setting up a fixed camera, he filmed himself dancing in empty, wrecked rooms, then edited the footage in a computer. The result, FloodHouseDances, constituted a five-minute triumph over loss.

Jody Weber tried something new for her concerts at the Cambridge Multicultural Arts Center. With the audience at little tables and treated to wine and cheese, Weber came out before each of the five dances to give an informal introduction, explaining a little about how she made the piece. The cabaret format isn’t new — José Mateo has been presenting his ballets that way in Harvard Square’s Sanctuary Theatre for years — but the talk part was a friendly attempt to educate the audience. Weber’s laid-back modern dances didn’t really need a lot of exposition, but what she chose to tell about them seemed either to focus on the obvious or to bring up questions I wouldn’t have thought to ask. The solos were fairly straightforward. For her own 49 Things, she said she’d made seven groups of seven unrelated movements, and as she practiced them, she learned how to connect them. She made Devotion’s Tale for Ann Fonte Abbott’s 50th birthday, a dance of gestures evoking remembered events in Abbott’s life.

Dancers hardly ever tell us the real information about composition. As Margie Pierce and Sarah Style performed Steadfast Season, you could easily see there was a fluctuating relationship between the two of them. But Weber’s remarks about how they were exchanging movement material made me look for this structural element. Exactly what moves were Pierce and Style exchanging, and how did this exchange take place? Did it matter to my enjoyment of the piece?