THE HISTORY BOYS: Alan Bennett’s Tony winner sets up a duel between knowledge for its own sweet sake and cogitating to a purpose. |

From Mr. Chips to Miss Jean Brodie, charismatic teachers have been the stuff of drama. But British writer Alan Bennett’s literate 2004 comedy The History Boys, which won the 2006 Tony Award for Best Play and was whittled into a film that same year, supplies more than one influential educator, setting up a duel between knowledge for its own sweet sake and cogitating to a purpose. In other words, it’s a debate that treads the same ground as that cynical joke alleging what an English major really needs to learn is how to say, “Would you like fries with that?” The erudite and eclectic Bennett, whose work runs the gamut from Beyond the Fringe to The Madness of George III, would certainly beg to differ.The History Boys, which is enjoying a warm and astute New England premiere from SpeakEasy Stage Company (at the Calderwood Pavilion through June 7), is set at a Sheffield grammar school in the 1980s. Eight middle-class sixth-formers — the boys of the title — are being groomed to sit for the Oxbridge exams, their heads crammed by the eccentric, Auden-inspired Hector with language and his passion for it and by glib young interloper Irwin with an exam-taking strategy that boils down to being cleverly contrarian in order to stand out. Some have seen the play as a metaphor for 1980s Thatcherized Britain, and it does include a song by the Pet Shop Boys. But to me The History Boys is more redolent of the 1950s, when Bennett himself was a non-public-school-pedigreed Oxbridge candidate (and the inept homosexual groping by Hector might more likely have been regarded as harmless). Throw in Robin Williams and some old school ties and you have Dead Poets Society with a higher IQ.

Bennett’s script is characteristically rich, contrasting not just two but three teaching methods — the boys are also mentored by Dorothy Lintott, a female historian who, after a career spent sifting through “five centuries of masculine incompetence,” believes in both the randomness of history and a firm grounding in the facts. And the complex comedy is as chock with glimpses into the human heart as with philosophies of education. Sometimes the two mesh, as in a scene where a subdued Hector walks the most sensitive student, Posner, through Thomas Hardy’s “Drummer Hodge,” conveying both its poetic significance and his own intimations of insignificance. True, the play is talky (an hour was cut turning it into the film), but what witty, provocative talk it offers — not to mention the snippets from old movies, the music hall, and, in director Scott Edmiston’s rendition, Adam Ant.

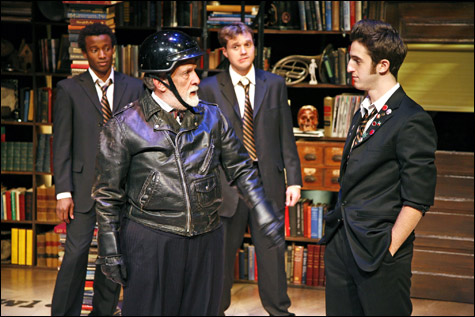

The SpeakEasy staging unfolds on a lofty library setting by Janie Howland that seems to contain not only a million musty books but also, in its tucked-away gewgaws, the very arbitrariness of history. With its various levels and orifices, the set works well for the choreographed entrances and exits (the history boys are not only classmates but something a of a vaudeville team bent on entertaining Hector), and Edmiston makes canny use of the carved wooden stair for the almost military campaigns of psychological and sexual aggression and retreat that pepper the play.

The production is also well cast, from Trinity Rep vet Bob Colonna’s rumpled, Shavian Hector to BU School of Theatre grad Karl Baker Olson’s prim, pursed, wounded Posner. Trinity’s excellent Timothy Crowe is a clipped commandant of a Headmaster, more interested in “results” than education, and Paula Plum, perpetually looking down over her glasses as if to assess the glitter of gold sweater guard and spectacles chain, is a wonderfully wry Dorothy Lintott. Chris Thorn makes a credible case for Irwin, whose exam strategies are probably right if regrettable, capturing the yearning ordinariness behind the flimsily cobbled hot shot. And the boys are a bright, sprawling lot whose standouts include Dan Whelton’s easygoing golden boy, Dakin, and Jared Craig’s Scripps, who has dedicated his testosterone to God. They all get into Oxford or Cambridge, but the play does not stop there — thereby perhaps proving the insubstantiality of such self-serving, short-term goals.

The theme of Americans in Paris singing up a storm — it worked for Gene Kelly, why not for Curt Columbus? Spurred by American films of the 1950s and ’60s set in some fictional gloss on the City of Light (and by a scheme hatched a decade ago to write a “hit gay musical”), the artistic director of Trinity Repertory Company spearheaded Paris by Night, which is now getting its world premiere from the Providence troupe (through June 1). He also wrote the book and lyrics, which were afterward set to jazzy melodies — some bouncy, some torching — by Chicago-based composers Andre Pluess and Amy Warren. Enthusiastically rendered at Trinity, the show feels like a labor of love, bursting with energy and a piquant period naïveté but certainly lacking the shelf life of An American in Paris.