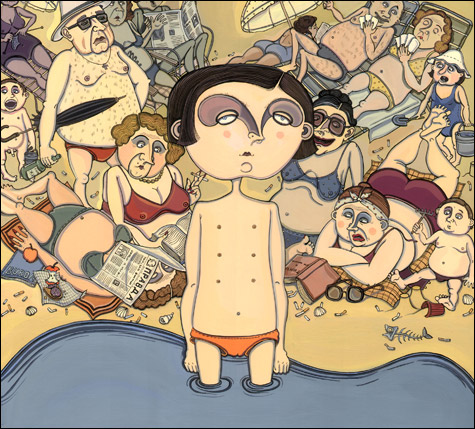

VENUS: Yana Payusova’s magic-realist cartoons are finely rendered, but her characters, all with the same exaggerated eyeshadow and bags under their eyes, are, well, repulsive. |

The aim of the DeCordova Museum’s Annual Exhibition is to round up “some of the most interesting and visually eloquent” New England artists. If that’s what the DeCordova’s Rachel Rosenfield Lafo, Nick Capasso, Dina Deitsch, and Kate Dempsey have actually found in the 11 individual artists and one collective they’re featuring in the 2008 edition, the result is a depressing report of the mostly bland state of art here.You’d think an exception would be the Boston collective the Institute for Infinitely Small Things, which by local curatorial and critical consensus (including me) is making some of the best art here these days. But those folks’ brand of conceptual art, which seems so funny and rascally and trenchant in tall tales passed by word of mouth and Web sites, falls flat here. Their formats suffer in a gallery. Shelves are lined with copies of the Institute’s The New American Dictionary: Interactive Security/Fear Edition, which professes to redefine the vocabulary of the “War on Terror.” It’s an acid satire of the Bush administration’s penchant for redefining terms like “torture” until they’re meaningless. But books don’t work well in art galleries, and if you crack these open, you’ll find that most of the words have been left with blank boxes for you to create your own definition. It’s an anti-climax.

A modest video shows Instituters, dressed in their trademark research lab coats, carrying piles of white boxes labeled “unmarked package” around Chicago last May in an absurdist quest to interview people about their post-9/11 fears, from lack of money to urban crime to terrorism. “I feel like somebody’s trying to make me feel more scared,” says one woman. The piece that works best as a gallery object is a Soviet-propaganda-style poster in which the Institute offers to transfer its patriotism to any interested foreign buyer in exchange for plane tickets to the buyer’s country and logistical costs. The transaction requires the parties to share an American drink and a local drink, repeating “those drinks until we all are drunk. At that point the transfer of patriotism will be complete.”

Swampscott’s Mitchel Ahern also addresses “War on Terror” lingo in linoleum-block-printed banners in the stairwell running from the lobby to the second floor. The text-based banners resemble letterpress prints or an ambitious A.C. Moore stamp-pad project. “I was dreaming of concentration camps.” “Don’t vote — you may be committing fraud.” “Mission Accomplished.” “Blue states secede.” “Free Martha ([Stewart].” The messages are not novel, but they are charmingly cheeky. A pair of scrolls reproducing texts from versions of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road fill a narrow three-story-tall wall. They’re just illustrations, but if you’re a fan of the book, they’re appealing ones.

Add to this stuff Bostonian Niho Kozuru’s cast rubber sculptures — which look like towers of gleaming, translucent, molded Jell-O — and you have the exhibition’s highlights. What’s missing? Anything from New England’s art powerhouse, Providence. Was there a more thrilling local art event in recent years than the secret apartment that conceptual pranksters built in the Providence Place mall? (When outed last September, they wound up on national TV.) And it would have been nice to see something by Boston-area folks like Andrew Mowbray, Deb Todd Wheeler, Mary O’Malley, Erik Levine, and the collective the Miracle 5, all of whom have produced standout work in the past year or so.

All the work in this year’s DeCordova Annual is proficient, but nothing wows — or freaks you out. The exhibit can be grouped into variations on a theme: landscape as digital animation or a little garden; family memories as deadpan photos or cartoony paintings; technology in painting as surreal scenes or gestural abstractions.

In Jamaica Plain artist Matt Brackett’s surreal oil painting, a woman stands in water under a pier at night waving her hand over glowing yellow waves, or a woman in a fur-collared coat scuttles across an icy marsh at sunset with her arm full of oranges. Brackett sketches out compositions, stages them with models, photographs them, pastes various photos together, and then paints the composites. It recalls the photos of Gregory Crewdson, which are alternately cheesy and seductively strange, like something from David Lynch or The X-Files. Brackett’s scenes head in this direction, but they can feel forced, like studio set-ups and still-life props rather than something plucked from dreams.

Another variation of technologically backed painting is Bostonian Mark Schoening’s black-and-white abstractions that look like splatters of mud and straw. They’re built from alternating layers of painting and digital print-outs of manipulated images of architectural fragments, but this part-man part-machine hybrid doesn’t come to life.