BLACK-ON-BLACK VIOLENCE Maalem depicts contemporary African savagery. |

Last weekend, as I sat in the audience for Compagnie Heddy Maalem’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) at Jacob’s Pillow, Zimbabwean strongman Robert Mugabe had just declared himself the winner of a presidential election for which he was the only candidate on the ballot. His triumph, if you can call it that, appears to have been engineered in part by having thugs go from house to house and beat every man, woman and child who was not supporting him. Opposing candidate Morgan Tsvangirai fled for his life and took shelter in the Dutch embassy in Harare.

Political juxtapositions came to mind because Maalem — a 57-year-old choreographer based in Toulouse, and with a background in both boxing and aikido — identifies himself as a child of war. He’s the son of a French mother and an Algerian father; his family fled North Africa when he was a boy. Yet whereas his familial fury is aimed squarely at the distortions of colonialism, his Le Sacre du Printemps, with 14 dancers hailing from Senegal, Togo, Benin, Mali, Nigeria, and Mozambique, takes on black-on-black violence. Maalem has headed unblinkingly into the dangerous territory of white projection. Igor Stravinsky’s 1913 evocation of a pre-Christian Russian fertility rite shudders alongside Maalem’s 2004 depiction of contemporary African savagery.

While considering a new version of Sacre, Maalem made an emotionally jarring trip to Lagos, Nigeria. As he explained to Jacob’s Pillow scholar Philip Szporer, he eased into the project with a simpler, thematically related exploration that became the 2000 short dance-for-camera work “Black Spring” created with filmmaker Benoit Dervaux. In “Black Spring,” the images race alongside the movement variations like flashes of memory. During Maalem’s Sacre, blurred representations are the backdrop to interludes of mechanical sounds by Benoit De Clerck carved into a recording of Pierre Boulez conducting the Cleveland Orchestra in the monumental Stravinsky score. Nature — swaying fronds and open water and blasted baobab trees — gives way to images of urban density in both sets of clips, as Dervaux’s camera sweeps across stacks of cloth, piles of garbage, and the overlapping corrugated roofs of shanties.

Maalem’s Sacre opens with two sculptural figures silhouetted against flashes of lightning. One bends to the floor, the other stands with her neck bent, hands clasping and opening like a spiny star. As the lights come up, the ensemble emerges onto the stage like cautious animals entering a glade.

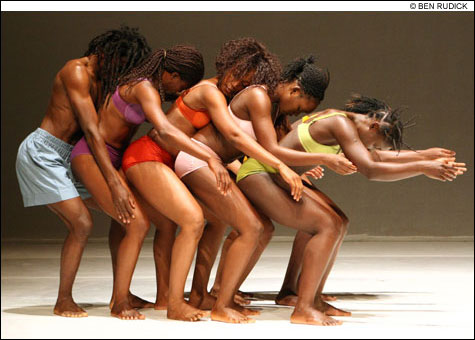

Maalem’s choreographic method builds on visual layering. Sometimes he achieves this by tight repetition in the ensemble, so that when the dancers in their brightly colored bathing suits and shorts start marching, their hips rocking, you have the sense that they could continue moving forward all day. Other times the massing of the troupe creates a sense of encroachment. As soon as a couple begin to nuzzle, the man rubbing against his partner’s leg and pelvis like an insistent kitten, the rest of the women line up behind her, replicating her positions and neutralizing the identity of the partners. When the men seize their female partners by the waist, dreamy coitus gives way to constraint and rape. Maalem stakes out the boundary between the communal mass and the unleashed mob.

In portraying mass violence, Maalem tends to overemphasize his literal references. During one of the interludes, two silhouetted men raise their arms and power them down. Are they portraying traditional African drummers? Soldiers assaulting a victim? Or are they are abstractions of some industrial motion? The ambiguity is probably deliberate, but in a work so didactic it’s unsatisfying. Maalem’s focus on the response of a horrified individual comes too late, though the solo by Dramane Diarra, twitching and helpless to cope with what he has seen, has the punch of hip-hop master Rennie Harris’s famous butoh-soaked solo in Facing Mekka. Metabolized by human bodies, this violent rite stains human conscience.