The myth of Orpheus is a Rorschach blot at which artists from Monteverdi and Gluck to Jean Cocteau and Marcel Camus have squinted over the centuries, seeing different and sometimes shifting shapes. Now in Orpheus X (at Zero Arrow Theatre through April 23), poet, composer, and performer Rinde Eckert gets to look into the ink, conjuring a rock-influenced opera about the seductive lures of art, mourning, and death. But in American Repertory Theatre artistic director Robert Woodruff’s fluid staging, with streaming video by Boston artist Denise Marika, the writing material, far from staying fixed in one Freudian blob, flows like honey (a nod to beekeeper Aristaeus), then crashes like loosed water, in an elemental work in which life is an urgent cacophony, death as peaceful as a museum.

The myth of Orpheus is a Rorschach blot at which artists from Monteverdi and Gluck to Jean Cocteau and Marcel Camus have squinted over the centuries, seeing different and sometimes shifting shapes. Now in Orpheus X (at Zero Arrow Theatre through April 23), poet, composer, and performer Rinde Eckert gets to look into the ink, conjuring a rock-influenced opera about the seductive lures of art, mourning, and death. But in American Repertory Theatre artistic director Robert Woodruff’s fluid staging, with streaming video by Boston artist Denise Marika, the writing material, far from staying fixed in one Freudian blob, flows like honey (a nod to beekeeper Aristaeus), then crashes like loosed water, in an elemental work in which life is an urgent cacophony, death as peaceful as a museum.

Eckert and Woodruff went Greek once before, in the 2003 Elliot Norton Award–winning Highway Ulysses, a Vietnam-infused rewrite of the Odyssey in which a traumatized vet traverses America, bearing a violent legacy toward his young son. Orpheus X is more minimalist, with just three singers/actors, a four-man band, and Marika’s pooling images of Eurydice caught in the vice of a coppery I-beam or floating naked down a long corridor to be processed into the next world. Eckert plays bereft rock idol Orpheus, whose Eurydice is not the wife carried off by snakebite while fleeing a rapist but a stranger with whom he becomes obsessed after a taxi in which he is riding bumps into her in the street and kills her. This Eurydice, an intellectual poet evidently too distracted to look both ways, dies in Orpheus’s arms, remarking how strange it is to cross over while cradled by a mega-celebrity. And the experience so affects the heretofore shallow rocker that he sticks with her from accident to emergency room to body bag, even absconding with her personal effects. These he sets up like relics at some cheap road shrine, retreating into his digs and himself — much to the chagrin of his agent and his rabid fans. “This is what he worships; things of no importance/This is what he worships; someone else’s trash,” scream-sings the agent, hurling from a plastic container the poet’s keys and his reading glasses.

The fourth character in the play is Persephone, Queen of the Dead, played by the graceful, otherworldly John Kelly, who doubles as John, the agent. In the latter guise, he bursts into Orpheus’s room in a long raincoat with lyrical reports of alarming cataclysms in the weather and a world that “has become a mad scramble.” As the regal Persephone, he greets newcomers to Hell with a questionnaire and the promise of a bath in the River of Forgetfulness followed by a slow fade into hard-won innocence.

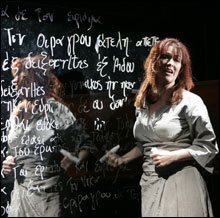

But Eurydice, played by lush soprano Suzan Hanson, goes more restless than gentle into that good night, haunting Hades with her unending, incomprehensible scribblings on glass. “When you die/When you die/They take your pens/They give you chalk,” laments the poetess as she progresses toward the underworld both in the flesh and on video. Chalk, says the Queen, is “just organized dust.” Nothing in Hell, she lightly assures, is indelible. This doesn’t stop the word-driven Eurydice as she travels among her stations of scratchings, surrounding her body (viewed aerially in the video) with white scrawl and painstakingly describing the rituals of her writing to an alert, interested Persephone.

Eckert has said in interviews that he wanted to give Eurydice agency rather than have her just be the loved thing Orpheus goes to Hell to get. Indeed, he makes her a deeper character than Orpheus, whose grieving seems little more than sullenness (though it’s clear he’s been affected by his obsession-triggering brush with mortality). Certainly as the piece opens, the ripe vocals allotted Hanson as she drifts into the playing space and toward the Underworld are more arresting than the pounding rock-and-roll re-creation of his dream of her death that Eckert has written for Orpheus, whom he plays in blue jeans and black T-shirt, his guitar hanging from him, when not in use, like a slack appendage. As for Kelly’s yearning Persephone, chained to Hades in fall and winter and to her mother, Demeter, in spring and summer, she pines for an autonomy she evokes in the song “Winter Alone.” In a neat twist, it is Eurydice who in the end gives Persephone agency, spinning the Queen’s dream of a solitary winter persona — “Standing in the snow by myself./Watching the smoke of my breath rising in the freezing air” — into a poem.