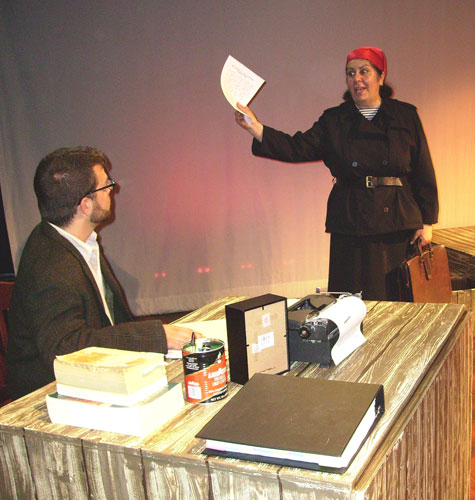

PROPAGANDA Deffet and Thomas. |

Such a difficult task, bringing horrific historical events to theatrical life. Ironically, the more vast the horror, the more difficult the challenge. Imagine the full sweep of something as enormous as the Holocaust reduced to stage scale.

David Eliet's Children of the Dnipro is touchingly well-intended, an empathetic cri du coeur being presented by his Apu/Anya Productions at Perishable Theatre (through June 14).

The 70-minute performance informs us about a little-known event called the Holodomor, the "Great Hunger," inflicted upon Ukraine in the early 1930s by Stalin. Millions died. The figure may be 2.6 million or 10 million, but the scale of the tragedy was enormous. Historians disagree about whether the starvation was intentional on Stalin's part, a way of weakening nationalism by enfeebling the population, or mainly a consequence of woefully incompetent central planning that also starved Russians.

Unfortunately, such facts remain in the forefront of this play instead of fading into the background. As a result, Children of the Dnipro comes across as an essay acted out more than vividly inhabited theater. While a single person suffering can open our hearts, we can be numbed by vast numbers — the killing fields of Cambodia, or Darfur.

The general suffering in Ukraine is particularized in a limited fashion here by grainy black-and-white photographs from the period, showing some of the emaciated children of the title, this one with frightened eyes, that one with scrawny legs and bulbous knees.

However, the central human focus is not on them but rather on a writer, Andriy (Peter Deffet). He is struggling to wrestle into the confines of the play all the distressing facts he has accumulated in his research. So the children are not only removed from us by time, but also by this filtering interpreter. (By the second photograph, I was yearning for the depicted child to emerge from the shadows and speak — through the playwright — for herself.) Andriy laments and re-laments his presumption in speaking for them, a crowning irony, since in going on so he is making his own sensitivity the main point here.

The set and costumes are by Ukrainian designer Pavlo Bosyy, who has the writer's desk on one side and images projected behind it, with a coffin-like box stage center, a pile of dirt in front of it. Several people give us and the writer information. A person billed as Comrade Woman (Patricia A. Thomas) wears a red babushka. She recites and defends various Stalinist edicts, such as those punishing collective farms that fail to meet their grain quota. One consequence encountered by peasants Olya (Kristina Drager) and Kostya (Luis Astudillo) is of bodies strewn across a field of rotting sugar beets — the farmers had been shot trying to gather the discards of what they had grown.

Other characters are a professor (Andrew Stigler), who accuses the writer of exploiting the children in the photographs, and a man in a lab coat (Jim Sullivan) who gives us a coldly analytical description of the effects of starvation and a strangely purposeless explication of the process of mastication, complete with illustration.

Any play on such a subject has us at mass starvation. Why amplify? Piles of bodies are far more affecting when imagined instead of counted. A little accomplishes a lot: tree bark ground into "a kind of flour," a powerful detail here, is diminished next to a mention of dead horses dug up and eaten. Too often, pathos slips into bathos: not only is a girl begging for crumbs at a bread line, but her emaciated collapsed body also is kicked to death by the callous store manager.

Playwright Eliet spent time in Ukraine a few years ago, as a director and a Fulbright scholar. In production information, he tells of a man saying that his grandmother was sent to a labor camp for seven years for stealing seven grains of wheat from the field of a collective farm after harvest. Someday, perhaps the story of that specific woman will be vibrantly imagined by the playwright in a play that shows more than it tells.