IMPROVISED, VAULTED, GREEN — call this the wood-thrush song of novels.

|

Laura Jacobs, who was the dance critic here at the Phoenix in the mid 1980s, is the author of Landscape with Moving Figures, a collection of writing from the New Criterion that's as polemic as it is poetic (no free pass for Mark Morris or Twyla Tharp, for starters). But she's also a novelist. Like Women About Town, which appeared in 2002, The Bird Catcher focuses on a young woman finding her way in 21st-century Manhattan (where Jacobs lives).

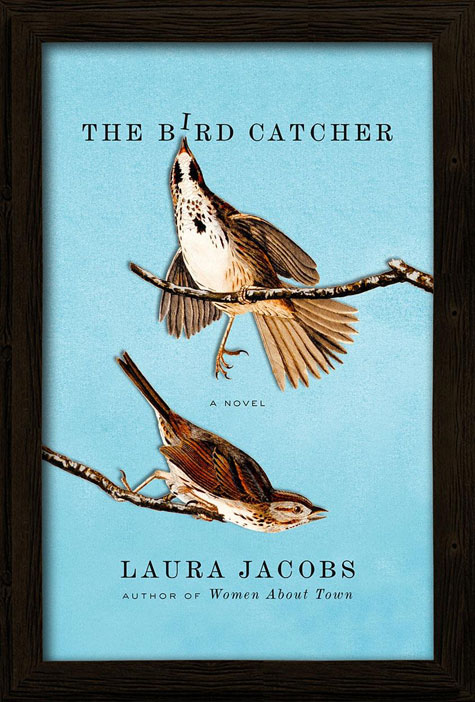

The Bird Catcher | By Laura Jacobs | St. Martin's Press | 304 Pages | $24.95 |

Margret Snow is a graduate student in Pre-Raphaelite art at Columbia University — that is, till she leaves school and takes a job as a window dresser at Saks. This decision is instigated in part by her ambiguous relationship with her substitute adviser, tall, dark, and handsome Assyriologist Charles Ashur. He's an avid birder, and so is she; that's how they get to know each other. It's gratifying to watch this witty, intelligent pair fumble toward each other, and demoralizing when, a few years after their marriage, his plane goes down on a birding trip to Newfoundland. Margret loses her job and is unfaithful to his memory before finding herself in dead birds, in stuffing them and bringing them back to life.Jacobs takes a tougher, more objective stance toward Margret than she did with Lana Burton, the aspiring theater and dance critic of Women About Town, and The Bird Catcher moves about in time in a way that can be disorienting if you're not paying attention. Of course, paying attention is what the book is all about; it's what Margret does best. Here she is on her way to the bird haven of Cape May in New Jersey:

You saw a lot of ghosts, driving alone at night. Shadows, coronas, and blurs; probably floaters too. Margret liked that, liked that sleeping-breathing feeling around her, the peace she felt being awake when others were lost in dream. Awake with the owls gliding on silent wings, deep and unseen in the fields, barn owls white as specters, great horned owls hoo-hooing the hour of the hunt. Awake with the night herons, their croaks under stars, their wing beats like oars. Awake with the mockingbirds, singing in the dark as if no one had told them the day was done. Blind troubadours, Margret once called them.

As Margret looks and listens, she creates an expanding galaxy of detail: the Hebrew word qippodh; the Gallery of Endangered and Extinct Species in Paris; Lyle the crocodile in The House on East 88th Street; a recipe for chicken soup (with the gizzard and the heart); Pretorius's bell jars in The Bride of Frankenstein; Manhattan's M5 bus route; Margret's "Insects of the Goldenrod" collection, with its snowy tree cricket and tiger-striped Eastern sand wasp. The human beings in her life are less fulfilling, for her and for us. Best friend Emily Edwards, who owns the trendy Chelsea gallery that opens the door to Margret as a shadow-box artist, has a style of her own ("a Modigliani inside a Braque," Charles calls her), and the money to wear Yohji. But Jacobs doesn't look as hard — or as sympathetically — at Margret's Saks co-workers, or at Sutton Place denizens Lee and Nan, who give a dinner party that's as instructive as it is interminable. Publishers Weekly's review deemed the book's characters "flat"; perhaps they're just painfully real.