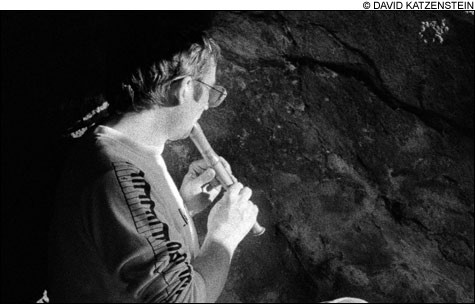

MUSIC AS A CONTINUUM: For Palmer (above), Roscoe Mitchell, the Gnawa clansmen of Morocco, Charles Mingus, and Darius Milhaud were all colleagues. |

| Blues & Chaos: The Music Writing of Robert Palmer | Edited by Anthony DeCurtis | Scribner | 480 pages | $30 |

“America’s Pre-eminent Music Writer Dead at 52” was the headline on Robert Palmer’s obituary in Rolling Stone after his liver failed in 1997. To those unfamiliar with Palmer’s extraordinary writing, that might seem like hyperbole. After all, the music-journalism arena includes such heavyweights as Nat Hentoff, Dave Marsh, Timothy White, Leonard Feather, Lester Bangs, and John Rockwell. But even among his fellow giants, Palmer towered. Not simply for his clarity, focus, and descriptive powers, but for his seemingly bottomless insight into every musical genre — and that included an ability to reveal connections between styles and players that were often oblique.Palmer saw music as a half-mystical continuum where Roscoe Mitchell and the Gnawa clansmen of Morocco and Charles Mingus and Darius Milhaud were all colleagues. And where magic could provide a defense against the chaos that was a subplot to many of his musical adventures.

Among the 60 essays, interviews, and profiles in this collection from Scribner edited by Anthony DeCurtis (who’s also a highly regarded music journalist and educator) are two examples of that weirdness. “Why I Wear My Mojo Hand” is a celebration of the anarchic spirit of bluesman R.L. Burnside, which emerges in a recording session that’s plagued by disasters until producer Palmer fashions a “mojo” bag of good-luck talismans. And there’s his conversation with Sun Ra, titled “Sun Ra Casts Special Light on Jazz,” where lamps blink off whenever the eccentric bandleader mentions the Egyptian sun god Ra.

Since Palmer kept a santería-like alter in his home, it’s likely he believed in the supernatural. But his musical knowledge was based on the hard facts he gathered while devouring every sort of music he could get into his ears.

He was born in Little Rock in 1945. As a teen, he single-handedly integrated Arkansas juke joints — first as a fan, and then as the only white member of the bands, playing saxophone and clarinet. After graduating from Little Rock University, he helped found the Memphis Blues Festival and played in the band Insect Trust — which took him to New York City when the group’s blend of jazz, folk, blues, soul, and rock got them a deal with Capitol Records in 1968.

His erudite writing began to appear in Rolling Stone in the early ’70s, and he was the chief pop critic for the New York Times (the first person to hold that title) from 1981 to 1988 before moving to Memphis to pursue freelance writing and musicmaking, and to take the house producer’s chair at Fat Possum Records. He made albums by Burnside and Junior Kimbrough for the Mississippi label that inspired a still-ongoing juke-blues revival.

Although Palmer contributed to many publications, among them the Phoenix, DeCurtis has selected mostly writing that appeared in Rolling Stone and the Times or as liner notes. Whether they’re examining Muddy Waters or minimalist composer Terry Riley, they are lively, penetrating, and inclusive.