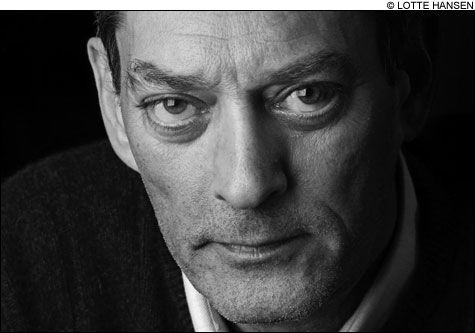

FICTIONAL TRUTH: For Auster's characters, storytelling is a way both to confront and to avoid fate. |

| Invisible | by Paul Auster | Henry Holt and Company | 320 pages | $25 |

To judge from the titles of some of his recent novels — The Book of Illusions, Oracle Night, Man in the Dark, and now Invisible — Paul Auster's fiction is receding, Samuel Beckett style, into non-existence. His books have always been stories about telling stories, but of late the stories themselves have been winding down and evaporating midway or trailing off — the solitary yarn spinning that's interrupted by the tales of real life in Man in the Dark being only a more egregious example.In Invisible, however, Auster takes a different route toward deconstructing his craft. Instead of subverting a single narrator, he bundles three together, with one of them writing by turns in the first, second, and third person, to provide a kind of one-man Rashomon of unreliable memory and inscrutable fate. Perhaps this complication is a distancing effect, an attempt to buffer the writer and reader from inescapable truths that would otherwise be too awful to bear. And indeed, the central narrative includes shocking violence, the breaking of a primal taboo, ruthless vengeance, and insidious evil.

That last is embodied in Rudolf Born, an arrogant, seductive, sadistic Conradian figure (or Dante-esque — Auster himself points out Rudolf's relationship to Bertran de Born in Canto 28 of Inferno) with shady connections to the French secret service and the debacles of Algeria and Indochina. Adam Walker, whose memoir this is, meets Born and his enigmatic paramour, Margot, at a boring party in 1967. A Columbia undergraduate, Walker wants to be a poet — if the draft doesn't get him first. Born dazzles him with his worldliness and out of the blue offers him big bucks to start a literary magazine. The allure of Margot sweetens the deal.

This, anyway, is the story Walker mails to his classmate Jim, a successful author with whom he hasn't been in touch since college. It's just the first chapter, and Walker wants Jim's advice in proceeding. He's stuck and he's running out of time — he's terminally ill. Jim advises Walker to switch points of view to get the story rolling again, and Walker complies, with succeeding chapters in the second and third person as the tale approaches increasingly unacceptable revelations. It is a literary game, perhaps, but as the author observes about the usage of vous and tu in French, "it creates a distance from both self and world that serves as a form of protection."

And so the manuscript continues, the narrative diminishing to bare minimalism as Walker's time runs out. Reading it, Jim notes, "Walker is vanishing from the world, he can feel the life ebbing out of his body, and yet he forges on as best he can, sitting down at his computer one last time to bring the story to an end."