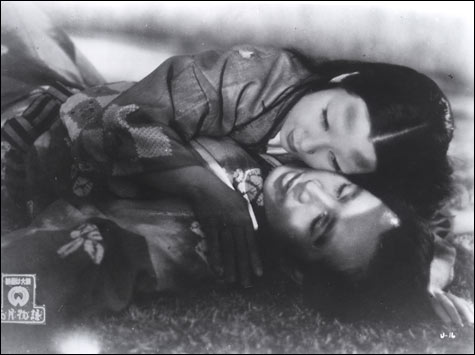

LIFE OF OHARU: How much is love worth? |

Love is in question in all seven films to be screened at the Museum of Fine Arts in a touring mini-retrospective of the work of Kenji Mizoguchi. The odyssey of the heroine of LIFE OF OHARU (1952; January 14 at 12:40 pm) begins when she, a high-placed lady at court, is told by a retainer that he loves her. For submitting to this persistent suitor, she’s cast out of court and into a life of uncertainties and humiliations. How much is love worth in Life of Oharu? As much as in SISTERS OF GION (1936; January 5 at 6 pm), whose story is complementary. The heroine, an ambitious young geisha, is punished for acting as if she didn’t believe in love; Oharu is punished for acting as if she did.In THE STORY OF THE LAST CHRYSANTHEMUM (1939; January 11 at 2 pm and January 12 at 5:45 pm), love drives the heroine to sacrifice her health to help her lover achieve glory as a kabuki actor. UGETSU (1953; January 5 at 4 pm) explores eroticism and familial devotion through a tale of a ceramics maker and his family in a time when feudal wars terrorize the peasantry. In SANSHO THE BAILIFF (1954; January 6 at 10:30 am), a parable about the dawning of the consciousness of justice, love between a mother and her children endures across years of separation and oppression.

His examinations of love lead Mizoguchi to pose the most fundamental question of cinema: what is time? His films deal with several kinds of time: history, for one, which is time encapsulated and made readable as a movement that it’s up to the viewer to prolong beyond the screening of the film. Sisters of Gion, a dense, compact film of destinies pressed together, is nothing but a furious rush of time, breaking off with a famous scene that hands everything over to the viewer. Although the pace of The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum is less hurried, the film’s construction in end-to-end tracking shots suggests a similar conception of time to that of the earlier film. There are other kinds of time in Mizoguchi. Life of Oharu slips back and forth through time, suggesting that the heroine’s journey is an endless ride in an infernal amusement park. The gravestone toward which the camera rushes at the end of Ugetsu marks a stop to the movement of history, suggesting that time is not a relentless progress toward the future but that it leaves landmarks, toward which it must turn back again and again.

UGETSU: History turning back on itself again and again. |

The highpoints of Ugetsu are three lateral camera movements: one at the beginning; one that marks an ellipsis of time during the hero’s sojourn at the palace of a mysterious noblewoman (complicating the question of what time is in this context, when the entire episode exists outside of the world); and the final shot that suddenly tracks with a boy who runs to place a bowl of water on a grave. These movements stand out for their sudden power of illumination (though the power they draw from is present throughout the film). The crane shot that links son and mother near the end of Sansho is rightly famous for a similar gathering of vaster perspective and increased intensity: as always in Mizoguchi, the greater distance of the camera entails no loss of commitment — a truth that can be forgotten in seeing the films on video but that is confirmed when they’re projected on screen.Although he was a master of his medium at least as early as 1933, Mizoguchi kept renewing himself. Life of Oharu shows the radical heightening of style for which he’s best known: it will also inform Ugetsu and Sansho. The presiding image of Life of Oharu is a fan: the opening title is printed on a fan; at one point in the film, Oharu works for her fan-maker husband; and the film itself unfolds in a fan-like space — a process that culminates in the stunning tracking shots in which the heroine rushes to follow a procession as it moves along the angled veranda of a palace. Throughout the film, space expands in all directions: the great sequence of a counterfeiter’s visit to a brothel ends with a long shot in which Oharu, alone on the upper balcony, views the sordid conclusion of the episode in the courtyard below.

Mizoguchi’s radicalization of style goes hand in hand with a radicalization of emotion. In telling the ghost story of Ugetsu, most directors would probably show the ghosts in such a way as to permit the rationalist, naturalistic interpretation that they exist only in the imagination of Genjuro, the bedazzled hero. Mizoguchi does the opposite: he makes the ghosts more real than the living man who sees them. The ghosts suffer, feel desire and sorrow, and one of them wipes her nose on her sleeve. The living man becomes an object tossed back and forth by bewilderment, desire, and fear, and then a surface on which magical characters are written.