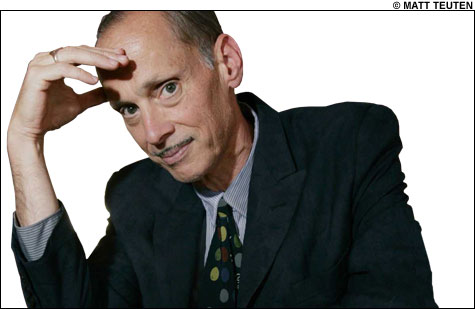

STILL WATERS: Director John Waters’s post-1981 films have been expensive and bland. |

The last resort of the true patriot is a fart joke.

What else can be done when lies, greed, cowardice, and entitlement stifle every other outlet for political protest and resistance?

There once was a time when raunchy humor and scatological satire were the weapons of choice for subversive voices to lampoon the establishment and the powers that be — in ancient Athens, for example, with Aristophanes, or Rome with Petronius, medieval England with Chaucer, and Renaissance France with Rabelais. And then, in the 18th century, there was the master, Jonathan Swift.

More recently, we’ve had Americans such as Mark Twain, Lenny Bruce, and George Carlin — all funny people who have aimed their profane, blasphemous, iconoclastic, and obscene wit at the absurdity and tyranny of oppressive regimes, ossified traditions, mind-boggling hypocrisy, and venal stupidity.

But, nowadays, blue comedy doesn’t necessarily mean blue politics.

So many of progressive to moderate bent, such as myself, have long taken it for granted that, if a movie is dirty and funny, its politics are probably okay. I first started to question this assumption, however, back in 2004 with South Park’s Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s feature film Team America. I was a big fan of their 1999 debut feature South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut. I thought these were guys with the courage of their radical, subversive, dirty-minded convictions, willing to take on the powers that be. But something must have happened to them in the intervening five years, because, in Team America — X-rated puppet sex notwithstanding — they can’t find any more formidable figures to eviscerate than ineffectual lefties Sean Penn and Susan Sarandon.

My misgivings grew with Jason Reitman’s debut feature Thank You for Smoking (2005). At last, I thought before the opening credits appeared, an acrid, black-comic satire about the corrupting power of lobbyists. But by the end, my expectations were confused, if not stymied, when the film seemed to be an endorsement of the profession.

And I needn’t go into my disappointment with Knocked Up, which uses its gleefully irreverent smuttiness to further a family-values agenda that could actually be embraced by Mitt Romney. Even Borat, with its nude wrestling and blatant irony, amounts at best to a takedown of such mighty institutions as redneck rodeos, drunken frat boys, and aging feminists. When it comes to the really tough targets (Alan Keyes?!), the equal-opportunity trickster Borat gets gun-shy.

So when the formerly hilarious Steve Carell turns bird-shit jokes into Bible lessons in Evan Almighty, or when the long-irrelevant but once-inspired Robin Williams does kicks-in-the-balls duty as a priest in the sanctity-of-marriage-boosting License to Wed, or when even the iconic enfant terrible John Waters has mellowed into the doting grandfather of a PG-rated musical by way of Broadway with Hairspray, I’ve got to wonder: what happened to the left’s monopoly of taboo-taunting, dumb-ass farce? Or was this tradition all just an illusion, one that crafty right wingers — or fence-sitting opportunists — have learned to exploit, masking their reactionary politics with sophomoric blasphemy and potty talk to lure in credulous, knee-jerk liberals?

A short history of raunch: Swift kicks

Like so much else that has been misunderstood, distorted, and exploited in our culture, the tradition of politically charged offensive humor goes back at least to the 1960s. That decade started auspiciously enough, with the election of John F. Kennedy, the New Frontier, and the Age of Camelot. Cracks emerged quickly, with the Bay of Pigs in 1961, the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, simmering racial turmoil, and the beginnings of the war in Vietnam. By the time Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, nobody was saying much about it, but everyone suspected deep down that the world was in the hands of crazy, stupid, and evil people with the casual capacity to destroy the human race with the push of a button.

Leave it to stand-up comics to first point out that the emperors had no clothes. Comics, that is, such as Lenny Bruce, whose legal busts for obscenity and for political honesty began in 1961. Movies were slow to catch on — the Production Code, a set of moral guidelines for the film industry, would cling to life until the switch to the MPAA rating system in 1967. Nonetheless, political satire of the black-comic, near-nihilist Swiftian variety arrived with John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962), an icy, absurdist thriller that conflated the Cold War and the American political process with incest, conspiracy, brainwashing, and assassination.

Stanley Kubrick and screenwriter Terry Southern took those notions to their logical and ludicrous conclusion in Dr. Strangelove (1964). Like Frankenheimer, Kubrick looked back to Swift, the greatest satirist in the English language, evoking in his masterpiece the devastating irony of A Modest Proposal and the allegorical grotesquerie of Gulliver’s Travels. He also shared Swift’s insight that all human abstractions and ideals spring from the basest physiological drives and functions. The Cold War, Strangelove gleefully demonstrates, didn’t spring from any conflict in ideology or between good and evil, but was the symptom of systemic sexual pathology.