XALA: Was it wife number one or number two who ruined our hero’s wedding night with wife number three? |

| “Ousmane Sembene: In Memoriam” | Harvard Film Archive | September 8-10 |

Hollywood has adopted a gentler, more insidious colonialism in regard to Africa. Stars embrace the continent’s orphans; studios make movies about its turmoil, injustice, and despair featuring white characters in the leading roles. Too bad Ousmane Sembene — who died last June at the age of 84 and whose short repertoire of films made over the course of 40 years screens this weekend at the Harvard Film Archive — never took up this feckless, patronizing brand of exploitation as a subject in a film. Perhaps he could have put everybody on mock trial, as Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sassako does the International Monetary Fund in his 2006 film Bamako.Sembene, as it happens, didn’t see much value in taking the foreign oppressors to task. The Africa of his films can’t afford to waste its valuable time and energy in blaming others. It needs to take responsibility for its actions, analyze the mistakes of the past, and move on.

Thus, when Sembene convenes a court or counsel of justice, it’s usually his fellow Africans who stand in the dock. His last film, MOOLAADÉ (2004; September 7 at 7 pm), is the one most seen outside the festival circuit, perhaps because its subject is one Westerners can understand and get indignant about: female genital mutilation. In a lively, hardscrabble Senegalese village, tough mother Colle refuses to allow her daughter, Amsatou, to go under the knife. Instead, she puts Amsatou and three other village girls under her protection, or Moolaadé, tying a string around her courtyard that, in the village’s tradition, magically keeps undesirables out. The patriarchs of the community are powerless against it; the best they can do is ban transistor radios, which they blame for giving their women newfangled ideas. And so the two sides remain deadlocked until the return of Amsatou’s Westernized fiancé, who’s made a fortune in Paris.

Moolaadé narrates its fable with deceptive simplicity, its Brechtian abstractions animated by rich characterization, earthy humor, and an eye for absurdist imagery. The film also boasts many of Sembene’s abiding themes and motifs: the power of fetishes; the impotence of post-colonial manhood; the slow ineptitude of institutions; the plight and the fortitude of women. He was one of the first and most committed feminist filmmakers — not just in Africa but in world cinema.

The fate of women lay at the heart of his first film, the neo-realistic black-and-white short “BOROM SARRET|CART OWNER” (1964; precedes La noire de . . .|Black Girl). Here the title laborer returns home, Vittorio De Sica–style, cartless. His long-suffering wife hands him the kid and heads out herself to make some money so they can buy food.

The trade she plies is left unstated, but it couldn’t be much more servile or degrading than that of the protagonist of Sembene’s first feature, LA NOIRE DE . . .|BLACK GIRL (1966; September 7 at 9:30 pm). Here a young woman from Dakar exults when she gets a job watching the kids of a French couple, and she rejoices even more when she’s asked to work for the family back home in France. There, however, she discovers she’s no more than a domestic slave — it’s The Nanny Diaries, with colonialism. The tribal mask she impulsively gave her employer as a gift hangs on the wall, a trivialization of her traditions and her humanity.

Although sometimes strident and repetitive in its anti-colonial rhetoric, La noire de . . . draws on an almost Godardian formal exuberance (a scene with the heroine in her Dakar boyfriend’s bedroom seems an allusion to À bout de souffle|Breathless), and it doesn’t condescend to caricature even the basest characters. What’s missing is Sembene’s distinctive humor, which emerges lustily in his next feature, MANDABI|THE MONEY ORDER (1968; September 8 at 9:15 pm). A postman delivers the title check for $15,000 to the two wives of Ibrahim, a pompous and unemployed but basically decent fellow. “Don’t kill us with hope!” one wife exclaims. Nonetheless, they buy a feast’s worth of food on credit, and word soon gets out to the neighbors that they’ve hit paydirt. Moochers looking for handouts crowd his courtyard, and Ibrahim grandiosely gives away the little that he has. When he arrives at the post office to cash the check, however, he’s stymied by red tape and sets off on a Jobian trail of humiliation by the system.

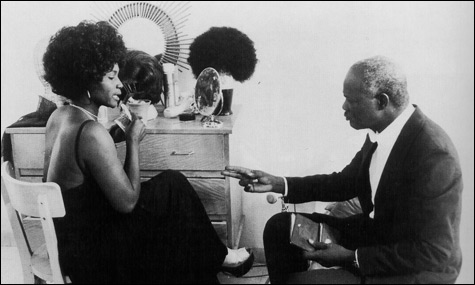

El Hadji, the hero of XALA (1974; September 8 at 7 pm), would laugh at Ibrahim’s folly. This film opens with people crowding the streets of Dakar to celebrate their independence, even as, inside the Chamber of Commerce, a ferrety Frenchman buys off El Hadji and the other new ministers with valises of cash. El Hadji can use it, since he’s just married his third wife. Unfortunately, someone — wife number one or number two? — has put upon him the curse of Xala, turning his wedding night into a disaster. Can he regain his manhood? Will renewed potency mean lost solvency?