STILL URGENT: Sporting a freewheeling narrative, an irresistible soundtrack, complex performances, and startling imagery, Z carries out its agenda with compulsive brio. |

| Z | Directed by Costa-Gavras | Written By Costa-Gavras and Jorge Semprún, based on the novel by Vassilis Vassilikos | with Yves Montand, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Irene Papas, Jacques Perrin, and Marcel Bozzuffi | Janus Films | French | 127 minutes | Museum of Fine Arts: December 9-14 |

John F. Kennedy wasn't the only political leader murdered in 1963. On May 22 of that year, Gregoris Lambrakis, a left-leaning, pacifist member of the Greek parliament and an aspiring presidential candidate seeking to replace the reigning right-wing government, was assaulted after a peace rally in Thessaloniki. He died five days later.In circumstances eerily similar to those of the JFK assassination, suspicions arose about the official explanation that the incident had been an "accident." The investigations of enterprising journalists and a principled prosecutor suggested otherwise — they connected the crime to the highest offices in the Greek government and in the US.

Greek filmmaker Costa-Gavras shot the story in 1969, adapting the novel by Vassilis Vassilikos; the result won a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar and established a template for muckraking political filmmaking used by, among others, Oliver Stone in JFK. Sporting a freewheeling narrative punctuated by scattershot flashbacks, an irresistible soundtrack by Mikis Theodorakis, understated but complex performances, and the occasional startlingly exact visual image, Z carries out its agenda with compulsive brio. Four decades later, this glimpse into the machinations of political violence, intolerance, willful ignorance, and systemic oppression has lost none of its urgent relevance.

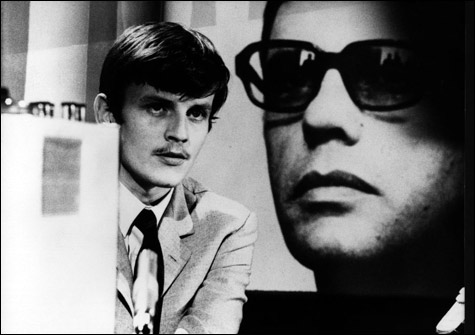

What's more, compared with Stone's efforts in this mode, Costa-Gavras's film shows greater sophistication and ambiguity. Not so much in the perpetrators' methods of violence or the intricacies of their conspiracy — the weapons of choice include careering vehicles and illiterate goons with clubs, and the cabal behind the killing is about as subtle as Glenn Beck and his teabaggers. Rather, the good guys here, on closer inspection, seem dodgier than your average crusaders for justice. Like the ubiquitous paparazzo (Jacques Perrin, resembling David Hemmings in Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up) who keeps popping up in crucial spots to question witnesses and snap pictures — not so much to uncover the truth as to get a scoop and a paycheck. Or the dogged prosecutor (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a right-wing red baiter himself, who in the end puts professionalism before ideology. Or the martyred hero. As played by Yves Montand, he's noble, photogenic, and inspiring. But what about that quick, Buñuel-esque flashback initiated by his glance at a woman adjusting a mannequin's wig in a shop window? And the bad guys are not without charm: Vago (Marcel Bozzuffi), one of the lumpen thugs, prances about with an anarchist joie de vivre only slightly undercut by Costa-Gavras's vaguely homophobic hints about his gay predilections.

In short, Costa-Gavras poses a philosophy of relativism and tolerance, of liberal, secular humanism, as an alternative to the fundamentalism of the right-wingers. But neither the heroes of the film nor the film itself made much headway in achieving such a reformation. A military coup in Greece in 1967 led to a dictatorship worse than the one that murdered Lambrakis. (It lasted until 1974.) As the film's stark coda points out, the new regime banned everything remotely suggestive of progressive values, from "A" (all works by Aristotle and Aristophanes) to "Z," a letter that in ancient Greek stands for the phrase "he lives."