STARTING AT ZERO: As befits the leader of a racially and sexually integrated band, Sly Stone had confidence that people were better than their prejudices. |

When Sly Stone sang “Listen to the voices” on the 1968 “Dance to the Music,” who could have known that, in just three years, voices of an entirely different sort would take him over? But when you listen to the rhythmic strands of nonsense syllables that provide the break in “Dance to the Music,” building tension until Sly and the rest of the Family Stone return in full euphoric force, it’s hard not to hear the buried, cryptic voices that crawl out of the recesses of the band’s 1971 There’s a Riot Goin’ On, a sound that would cause Greil Marcus to call the album “golem music.”

Three years. Not too little a stretch of time for a ’60s performer to end up at a place that would have been unthinkable when he started. That was the time it took the Beatles to go from A Hard Day’s Night to Sgt. Pepper, Dylan from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan to Blonde on Blonde. But no one besides Sly Stone in effect ended his career with the implicit message to his audience that what had come before was a lie. There were records after Riot, just as Jean-Luc Godard made movies after Weekend. Yet if the music that preceded Riot still sounds too good and too true to be a lie, the finality of the album cannot be argued with. For Sly, it was the equivalent of the finish of Weekend, when the title “Fin du cinéma” made it seem as if Godard had just jumped off the planet.

There are other albums to talk about — six, in fact — in the new Epic/Legacy limited-edition box set Sly and the Family Stone: The Collection. (They’re also available individually.) But with the exception of the 1969 Stand!, they’re all swallowed into the black hole of Riot. The attraction of this long-overdue reissue series is the remastered editions of albums that have been unavailable or available in cheap first-generation CD configuration. The bonus material to be found is mostly instrumentals and a few edits for the singles market. None of it is memorable. Worse, Epic/Legacy has failed to include the non-album singles. Which means that you can blow $70 on this set and still come home without the essential “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” and the band’s most beautiful song, “Everybody Is a Star.”

The uneven early records show Sly itching to encompass all the music he can. (The first track of their first album, 1967’s A Whole New Thing, opens by quoting “Frère Jacques.”) But, really, a perfectly good S&TFS library can be built from Stand!, Riot, the old (1970) Greatest Hits, and Fresh, the album that followed Riot and includes the great “If You Want Me To Stay” and Sly’s indelible duet with his sister Rose on “Que Sera, Sera.” That version of the Doris Day standard turns it into a languid, emotionally tough blues, the sound of a black mother saying to her children, “Don’t count on anything in this world.”

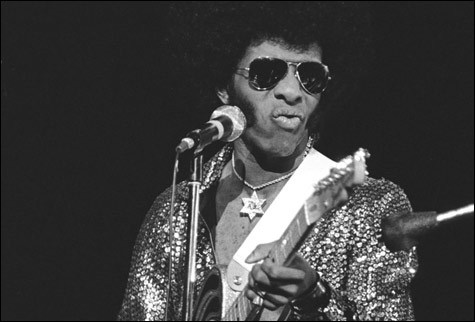

It’s not that the utopian cast of the band’s early work has ignored harsh realities. You don’t record a number called “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey (Don’t Call me Whitey, Nigger)” if you’d like to teach the world to sing. But as befits the leader of a racially and sexually integrated band, Sly had confidence that people were better than their prejudices. And though his huge Afro and the outrageous clothes he and the band wore made him beloved of the freaks, he wasn’t arrogant enough to try to keep the squares from dancing at his revolution. “I am no better/And neither are you,” he sang on “Everyday People,” and he expanded that thought on the gorgeous “Everybody Is a Star,” which had the grace to believe that people will rise to the occasion life presents to them and them alone.

All these threads come together in the showstopping celebration that is Stand! The album is studded with hits: the title song, “Everyday People,” “I Want To Take You Higher.” It’s big and flashy, a band showing off what they can do, and at the same time so welcoming they draw you into their embrace.