"People were mellow and watching the movie, and, as the credits were rolling, Kenny pushes Jimmy Cliff in front of the screen with the projector shining on him," recalls former WBCN Program Director Sam Kopper, who that night recorded the Orpheum show in Crab Louie Studios, the Boston school bus he had converted into two-thirds hippie motor home and one-third radio-control room. "You can imagine the state of mind — people were smoking boom here and there and everywhere. You could smoke pot in hip restaurants back in those days."

A movement was born — from that moment on, Cambridge staked a claim as the place to go on a Saturday night to get sweet and dandy. One of the many dreadlocked white boys who frequented those legendary bong-a-thons and the concerts that sprung up in their wake was Peter Simon, who would go on to become reggae's most celebrated photographer. Simon — a 1970 Boston University grad who is regarded by reggae's cognoscenti as highly as his sister Carly is by folk-pop fans — had a major hand in accelerating the course of reggae in America.

"Before hearing Jimmy Cliff, I was a Woodstock lunatic," says Simon, who was also the founding staff photographer of the original Cambridge Phoenix back in the late 1960s. "I listened to the Beatles, the Stones, and Dylan, but then the music business got too corporate. Even WBCN — which was very anti-establishment — turned industrial. I loved going to see [The Harder They Come]; the kind of people that movie attracted were the kind of people who I was attracted to."

While smoking a joint on a Martha's Vineyard beach in the summer of 1975 — the same year Bob Marley did 14 consecutive shows in seven days at the now-defunct Paul's Mall on Boylston Street, and one year before Peter Tosh would record his critically applauded Live and Dangerous album at the same venue — Simon and a BU pal, budding music journalist Stephen Davis, presciently decided that someone had to chronicle reggae's embryonic development in the US. They followed up the premonition that fall by writing and snapping visuals for a prominent feature in the New York Times. That piece in turn led to their watershed 1977 tome, Reggae Bloodlines — which brought Davis's typewriter and Simon's camera overseas "in search of the music and culture of Jamaica" — and the subsequent stateside exposure that it generated for the music. Those in the know will tell you: Boston — as much if not more so than New York or any other American city — helped launch reggae in the States.

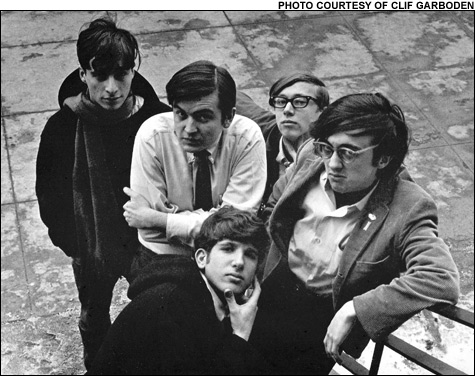

LOCAL BOYS: Stephen Davis (far left) and Peter Simon (kneeling) — shown with BU buddies (and Phoenix colleagues) Joe Pilati and Clif Garboden, as well as Ray Mungo — would collaborate on a New York Times feature on reggae that would later be developed into the seminal book on the genre, Reggae Bloodlines. |

New bloodlines

Whereas other niche genres have given up on college radio and focused their grassroots-marketing efforts online, reggae — especially in Boston — has, over the years, connected with its core audience through campus and pirate airwaves. There's currently more than 200 hours of Caribbean programming showering the area inside of Route 128 — about the same, or maybe even more, than in New York City. That's notable in that the latter has a Caribbean population north of 600,000 people, roughly 13 times the size of that in Boston. Which is not to say that the Hub's island demographic is unsubstantial; according to the 2000 census, Caribbean natives make up 29 percent of Boston's foreign-born population — more than Africans, South Americans, Central Americans, and Mexicans combined. More than 13,500 Jamaicans, Trinidadians, Barbadians, Dominicans, and Haitians immigrated to Boston between 1990 and 2000 — 14 percent of them from reggae's Graceland, and the rest anxious to harness the vibe and invent fresh interpretations. Even Dominicans and Puerto Ricans — who have never been much of a reggae audience, historically — have jumped on board with reggaeton. (In the past two years, both Don Omar and Daddy Yankee have crammed the Orpheum.)

Tropical radio's popularity is not just a recent development — deejays have been breaking records in these parts since before Bob Marley played his fifth-to-last show ever at the Hynes Auditorium in September 1980. The first reggae-oriented radio show broadcast on the East Coast was, by all accounts, Peter Simon's Reggae Bloodlines (named after his book, which — by the time of the show's premiere in 1977 — was a commercial success) on Brown University's WELH. In 1980, Simon brought his vinyl to "the very hip low-wattage" WCAS in Cambridge, then the following year to WGBH, where he was soon after fired for endlessly campaigning for marijuana legalization. "That show brought in the most money during fundraisers," says Simon. "But after that — after being the major exponent of reggae in Boston for years — I bowed out of my Boston reggae persona and moved to Martha's Vineyard."