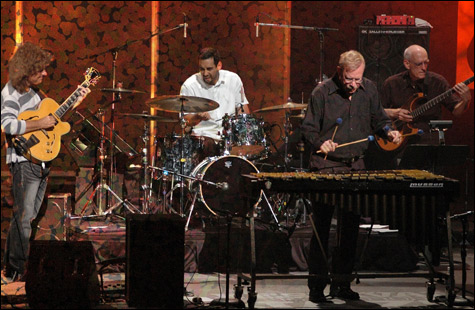

THROWING IT DOWN: When Burton and Swallow (here with Pat Metheny and drummer Antonio Sanchez) heard the Beatles at Shea, they were galvanized. |

As an aspiring young jazz musician in the late '50s, Steve Swallow recalls having "nothing but disdain for popular music and for the electric bass as well." He didn't hear "the first rumblings that there was music outside jazz that was worthy of attention" until he noticed in 1961 that his friends Carla and Paul Bley often had Supremes records playing at their house. "At first, I was amused and perplexed by Carla's obvious devotion to this music and her obvious regard for it." Eventually, he says, "I began to get it, I began to catch on that there was something really powerful there."

This may come as a shock to fans who know Swallow as a master of electric bass — someone who transformed the conception of it as a jazz instrument — and, in Gary Burton's quartet of the late '60s and early '70s, as a key player and composer who helped introduce the language of guitar rock into jazz. But his transformation was a shock for Swallow as well.

"The jazz community at that time was incredibly strict and stern, formidably so," he explains over the phone from his home in Woodstock, New York. "It was really heretical when we started growing our hair long and playing a lot of straight-eighth-note music."

Starting with the RCA album Duster in 1967, Swallow and Burton began to change all that. They worked with Larry Coryell, an electric-guitarist under rock's spell, and the great jazz drummer Roy Haynes. Currently, Swallow and Burton are having a reunion of sorts with a later guitarist from the band, Pat Metheny, plus drummer Antonio Sanchez. They've just released Quartet Live (Concord; recorded in 2007 at Yoshi's in Oakland), and they play the Berklee Performance Center on Saturday and Freihofer's Jazz Festival in Saratoga on Saturday the 27th.

But back to those early years. The turning point on the path to Duster came when Swallow, Burton, and another couple of friends sprang for third-base seats at the Beatles' 1965 Shea Stadium concert. "Gary and I were really moved by the music that night, and by the cultural aspect of the event. It was the first time I'd been in a public place where dope was openly smoked. There was a lot of stuff ancillary to the music but important nevertheless. But at the core of it was this band that was playing great. And three composers — four if you count 'Yellow Submarine.' And they were indisputably throwing it down. That concert set us off, and it galvanized my intentions to bring some of that into the music I was playing."

The die was cast. When I get Burton on the phone at his home in Fort Lauderdale, he recalls being attracted to the different kinds of harmonies in rock — "triads and chords that don't move to the same resolutions that we were used to in jazz." It was the kind of music that comes from writing for guitar instead of piano. And there were those "even eighths," so antithetical to jazz's swing pulse.

There was something else that Swallow noticed at that Beatles concert. "I was impressed by their posture toward their public — they were extending themselves to us in a way that I admired and wanted to emulate. They were addressing us, but with a lot of dignity, without any condescension on one hand or groveling at our feet, either. They were tremendously contained and dignified." What's more, the white English band "talked openly about their debt to black American music."

Other revelations were to come. The Burton Quartet often traveled cross-country, and Swallow says he first heard Jimi Hendrix on the radio in a VW bus crossing the Golden Gate Bridge — a moment he compares to "Paul on the road to Damascus." The quartet grew their hair, donned beads and bellbottoms. Like other jazz acts, they were regular openers at Bill Graham's San Francisco Fillmore Auditorium for bands like Cream and the Electric Flag. Swallow: "It was impossible for me to deny that I was listening to music of real value and real meaning for its time. And I'd begun to question whether the jazz music I'd grown up admiring so much was still congruent, still as germane in the late 1960s as it had been in the late 1950s." As he wrote for the band, Swallow consulted its guitarists — Coryell, and later Sam Brown, John Scofield, Mick Goodrick, Metheny — to translate "guitar-neck vocabulary" into themes that could become content for jazz improvisation. Burton himself had recorded as a teenager in Nashville with country guitarist Hank Ballard and, later, Chet Atkins.