When people think reggae, the first name that comes to mind is Bob Marley. Far fewer know the name of the man who not only gave Marley and the Wailers their start but who was perhaps more instrumental in laying reggae’s solid foundation than any other individual: Clement “Coxsone” Dodd. A sound-system innovator, record producer, and the first black studio owner in Jamaica, Dodd parlayed entrepreneurial acumen and impeccable taste into one of the largest legacies in recorded music at Studio One, his studio and label. Studio One played a central role in the Jamaican ska, rocksteady, and reggae booms of the ’60s. And much of that music is now being reissued by the Rounder imprint Heartbeat.

When people think reggae, the first name that comes to mind is Bob Marley. Far fewer know the name of the man who not only gave Marley and the Wailers their start but who was perhaps more instrumental in laying reggae’s solid foundation than any other individual: Clement “Coxsone” Dodd. A sound-system innovator, record producer, and the first black studio owner in Jamaica, Dodd parlayed entrepreneurial acumen and impeccable taste into one of the largest legacies in recorded music at Studio One, his studio and label. Studio One played a central role in the Jamaican ska, rocksteady, and reggae booms of the ’60s. And much of that music is now being reissued by the Rounder imprint Heartbeat.

In addition to issuing hundreds of albums and countless hit singles, Studio One boasted a house band featuring the island’s finest players. Having cut their teeth in Kingston jazz bands and on the hotel and cruise-ship circuit, they were versatile virtuosos. Under the guidance of Dodd and his team of crack engineers — among them, Sylvan Morris and a young Lee “Scratch” Perry — Studio One’s band produced a corpus of backing tracks, or riddims, that would outpace even the original songs recorded on them, providing what has amounted to a Jamaican “Real Book,” of sorts. These riddims and recordings (sound quality is crucial to their character) have been versioned, re-licked, and sampled thousands of times over.

It was Dodd’s engagement with American culture — in particular, the music of African-Americans — that would prove his ticket to success. The sound of Studio One — a sound as engaged with contemporary R&B and soul as with Jamaican folk and pop traditions — expressed a new sort of cultural alignment for many Jamaicans. Jamaicans tuned into the sounds of America via radio broadcasts. Dodd himself was inspired by the jive-talk stylings of black radio DJs and began collecting R&B records while working in Florida. He returned to Kingston with big speakers and big plans. Before long, “Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat” was the eminent sound system (the name for mobile discos with stacks of speakerboxes) on the downtown scene.

As Dodd relates in liner notes to the reissues — The Best of Studio One,Full Up: More Hits from Studio One,Downbeat the Ruler: Killer Instrumentals from Studio One, and Bob Marley and the Wailers: One Love at Studio One 1964-1966 — when the American music industry shifted from R&B to rock and roll, he decided to meet the dancehall’s demand for more boogie-woogie and jump blues. The Jamaican music industry began advancing a sound as local as it was international. And Studio One became its premier outlet.

After Jamaica’s most popular ska group, the Skatalites, broke up in the mid-’60s, trombonist Don Drummond and keyboardist Jackie Mittoo became the core of Studio One’s house band. When ska yielded to rocksteady’s bubbling, electric basslines, soulful group harmonies, pop-idol balladry, and rude-boy attitude, Studio One elevated singer Alton Ellis and groups like the Heptones into the national spotlight and onto the charts. And when, around 1968, a new style evolved — a style which, with its popping organs, echo-laden guitars, and hard “one-drop” drums, seemed to embody the ragged, rugged character of the place that produced it — Studio One remained at the forefront, producing some of the earliest recordings now identified as reggae.

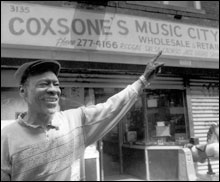

Dodd passed away in May of 2004 (just days after seeing Brentford Road re-christened Studio One Boulevard). But his sounds are being resurrected by Heartbeat — a new beginning for an old relationship. Heartbeat began re-releasing Studio One material shortly after Dodd moved his operations, including a record shop, to Fulton Street in Brooklyn in the ’80s. Since ’83 more than 250 reggae albums have had the Heartbeat imprint, including more than 60 from Studio One. At the helm of the reissue series is the same person who has overseen all of the label’s Studio One releases, Chris Wilson, a Jamaican-born Boston transplant.

Dodd passed away in May of 2004 (just days after seeing Brentford Road re-christened Studio One Boulevard). But his sounds are being resurrected by Heartbeat — a new beginning for an old relationship. Heartbeat began re-releasing Studio One material shortly after Dodd moved his operations, including a record shop, to Fulton Street in Brooklyn in the ’80s. Since ’83 more than 250 reggae albums have had the Heartbeat imprint, including more than 60 from Studio One. At the helm of the reissue series is the same person who has overseen all of the label’s Studio One releases, Chris Wilson, a Jamaican-born Boston transplant.

Thanks to his long-time relationship to Dodd, Wilson has access to original tapes and even the machines on which they were recorded. As a result, Heartbeat’s remasters retain the strength of the originals. And, having played for years with Boston’s I-Tones, Wilson knows how big the bass should be, how crisp the percussion, how clear the voices, how warm the sound.