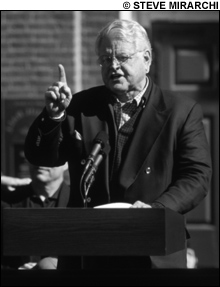

Once upon a time, no one whipped up conservative rage like Ted Kennedy. Back in the day, the senator from Massachusetts wasn’t just a misguided Democrat — he was the Liberal Great Satan, a genuine menace to all things good and holy.

Once upon a time, no one whipped up conservative rage like Ted Kennedy. Back in the day, the senator from Massachusetts wasn’t just a misguided Democrat — he was the Liberal Great Satan, a genuine menace to all things good and holy.

Consider Teddy Bare: The Last of the Kennedy Clan, a 1971 screed by Zad Rust dedicated to the accident that killed Mary Jo Kopechne two years earlier. The circumstances of the case were ugly: after driving his car off a bridge and into the waters of Poucha Pond, Kennedy swam to safety and fled, instead of immediately notifying the police. By the time the car was dragged to the surface the following morning, Kopechne was dead.

For author Rust, a fervent anticommunist with a conspiratorial streak, Chappaquiddick epitomized the gulf between Kennedy myth and Kennedy reality. As such, it offered a final chance to open America’s eyes. Like his brothers before him, Ted Kennedy, Rust warned, is “one of the prominent operators chosen by the Hidden Forces that are hurling the countries of Western Civilization toward the Animal Farm world willed by Lenin and his successors.” If Ted Kennedy were elected president, he concluded, a “satanic utopia” would result.

Heavy.

Today, however, the Clintons have replaced the Kennedys as the primary objects of conservative rage. Not only do Bill and Hillary embody the same alleged vices (ruthless ambition, shocking immorality), but they’re also far more powerful. Ted Kennedy may still be the “Liberal Lion of the Senate,” capable of stirring the Democratic faithful at key moments. But after serving in the US Senate since 1962, he’s also an old man (74, to be precise). He’ll never be president. And after dispatching a series of strong Republican challengers, it’s clear he’ll never lose his Senate seat.

Kennedy hatred, in turn, has become a political relic. Last week, at a shindig for young Boston-area Republicans, I asked Jay Cinq-Mars — a Northeastern student managing college outreach for would-be Kennedy challenger Kevin Scott — about his boss’s possible opponent. In response, Cinq-Mars actually offered praise for the man Republicans used to love to loathe. “I’m not going to lie — he’s still got it,” Cinq-Mars said. “He’s been in there forty years, but when he’s prepared, from what I’ve seen, he’s very charismatic. His arguments are very flawed, when you think about them, but when you hear him speak, he presents them very well. He’s very captivating.” Talk about a generation gap.

Kennedy as GOP kingmaker

Just after Chappaquiddick, it would have been foolish to bet on Kennedy’s long-term political future. He ran unopposed in the 1970 Democratic primary, but more than a quarter of Democrats opted not to vote for him. In the 1970 final, meanwhile, Republican Josiah Spaulding pulled in 37 percent of the vote. Considering the Kennedy clan’s status as de facto Massachusetts royalty, these numbers suggested that Teddy was damaged goods.

But he wasn’t — at least not fatally. In the coming decades, no Republican challenger ever came close to knocking off Kennedy. Still, he did attract a string of credible, aggressive Republican challengers. Each generated passion among the conservative faithful, and each went on to become an icon among Massachusetts Republicans.

In 1982, Ray Shamie ran a solid race, pulling in 38 percent of the vote to Kennedy’s 61. After making one more unsuccessful Senate run — he lost to John Kerry, 55 percent to 45 percent, in 1984 — Shamie took the reins of the Massachusetts GOP, where he helped orchestrate Bill Weld’s 1990 gubernatorial victory. Six years later, Kennedy beat back Joe Malone, winning two-thirds of the vote. Malone later parlayed this high-profile defeat into a successful run for state treasurer; today, though out of office, he remains one of the state GOP’s major figures.

Then came the 1994 election cycle, which saw Republicans run their strongest Kennedy opponent yet. Mitt Romney lost, just like his predecessors. But by pulling Kennedy below the 60 percent mark — and cracking 40 percent himself — Romney gave the GOP a legitimate moral victory. He also boosted his own career prospects: eight years later, he was elected governor of Massachusetts.

Then came the 1994 election cycle, which saw Republicans run their strongest Kennedy opponent yet. Mitt Romney lost, just like his predecessors. But by pulling Kennedy below the 60 percent mark — and cracking 40 percent himself — Romney gave the GOP a legitimate moral victory. He also boosted his own career prospects: eight years later, he was elected governor of Massachusetts.

The pattern was clear: by taking on Kennedy, promising young Republicans could make their names statewide and become forces in the Massachusetts GOP. Obviously, this was good for the people in question. But it was also good for the state Republican Party, which had hemorrhaged influence throughout the second half of the 20th century and needed all the young stars it could get.