The novel plays off Carlotto’s autobiography. He was a member of the radical left-wing Lotta Continua, the Ongoing Struggle. Implicated in a murder, he was acquitted, then re-arrested and retried. He escaped to South America but eventually came back to Italy to turn himself in. It took 18 years to clear himself, eight of which he spent in prison. Today he is the reigning king of Mediterranean noir; his “Alligator” detective series has made him one of the most popular authors in Italy.

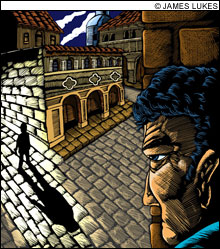

The American noir hero/anti-hero was a wiseacre. He held hard to his Emersonian individualism. He pooh-poohed the idea that he might have any redeeming features. Books and films showed psychological portraits of alienated and ascetic guys who might have been good, if things hadn’t gone bad. They used the language of the street and the poetry of violence, and, in the guise of genre writing, critiqued social corruption (“It is not a fragrant world,” Raymond Chandler said) in a way that highbrow literature couldn’t seem to.

Hammett and James M. Cain’s bleak portraits of modernity spoke not only to Camus and Sartre, but to succeeding generations of writers who have appropriated the form — crime fiction with noir’s characteristic dark fatalism — and turned its penetrating gaze on their own societies.

The protagonist of Jean Claude Izzo’s Total Chaos (Europa; originally published in 1995, and set in the early ’90s), Fabio Montale, illustrates the difference between the American- and Mediterranean-noir hero. He values, above all else, loyalty to the friends he grew up with in the projects of Marseilles. Despite the fact that he’s a cop and they are criminals, their shared heritage — the children of hard-working Italian and Spanish immigrants fleeing Mussolini and Franco, they “did the jobs the French wouldn’t touch” — bound them. A sense of community and a debt of honor draw Montale to the old neighborhood to investigate their murders.

The protagonist of Jean Claude Izzo’s Total Chaos (Europa; originally published in 1995, and set in the early ’90s), Fabio Montale, illustrates the difference between the American- and Mediterranean-noir hero. He values, above all else, loyalty to the friends he grew up with in the projects of Marseilles. Despite the fact that he’s a cop and they are criminals, their shared heritage — the children of hard-working Italian and Spanish immigrants fleeing Mussolini and Franco, they “did the jobs the French wouldn’t touch” — bound them. A sense of community and a debt of honor draw Montale to the old neighborhood to investigate their murders.

To solve the crime, he must negotiate the street gangs, corrupt cops, and Mafioso of the crumbling projects, and battle the rising neofascist and fundamentalist movements. The chapter headings are a poetic shorthand for Montale’s real and existential struggle: “In Which the Most Honorable Thing a Survivor Can Do Is Survive”; “In Which at Moments of Misfortune You Remember You’re an Exile.”

Izzo, who died in 2000 at the age of 55, scatters his prose with song lyrics, poetry, and fantastic descriptions of the sun-dazzled, sordid city. The austerity of American noir is supplanted by every sensual delight Marseilles has to offer: beautiful women, perfectly grilled sea bream with aioli, copious amounts of rosé and pastis.

The novels of Leonardo Sciascia (1921–1989; pronounced “shasha”), recently released by the New York Review of Books Classics series, are the most elegant of the Mediterranean detective fiction. Sciascia’s writing owes more to Pirandello and Calvino than to Hammett or Chandler. Both lyric and ironic, his prose reveals a stratified Sicily, the island’s inhabitants embedded and held by each layer of sediment: church, family, political party, and Mafia. All are bound by a code of silence and resigned to the way things are, always have been, and always will be.