Choreographer Tim Rushton makes unusual, high-powered dance movement and blends it with slick but modest theatrical appurtenances, sound scores that claim your attention, and important program notes. Rushton’s Danish Dance Theater had its Boston debut at the Paramount Theatre last week, courtesy of the Celebrity Series, and all four pieces on the program carried expressionistic weight as well as philosophical stimulus.

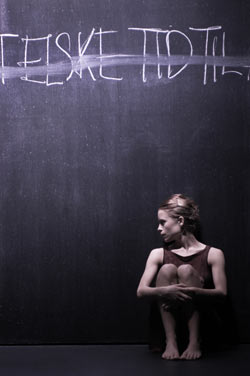

KRIDT (CHALK) The writing on the blackboard is, like life, not permanent.

|

The company seems to be working in a sort of post-Tanztheater mode.

Tanztheater, the genre precipitated 30 years ago by Pina Bausch, aimed to apply a populist reform to dance’s high culture — hence, the “everyday” look of the movement, the “personal” contributions of the individual dancers, and the psychologically loaded situations they were always embroiled in. We haven’t seen much Tanztheater in Boston, and by now it’s spread out and diversified to serve many objectives. I felt its tinge in the Danish Dance Theater’s slightly glitzy designs, and in the program notes promising existential relevance.

Like many contemporary dancemakers, Rushton choreographs in a made-up, high-intensity vocabulary layered with the signifiers of a bigger intellectual universe. The movement may remind you of something you’ve seen people do on the street, but it’s all more complicated. In the program opener, Shadowland (2002), dancers walk on like runway mannequins: every sector of their torsos makes an attention-getting ripple on every step. But, sinuous as this movement is, the dancers seem curiously sexless. The three women and three men expand in big, in-place, winding, wheeling moves and explosive spiky hits. Two of them begin a duet wrapped tightly together, then finish with slow, spread-out airplane lifts.

Shadowland is based on recorded texts from the Beat poets — Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and their companions. As Ginsberg intones his “Holy” epilogue to Howl, the word “holy” appears in projected blocks on the floor. Later, I thought the dancers were shaping their gestures to the rhythm of Ken Nordine’s word jazz. At the end of the dance, people slowly lay down on the holy-imprinted floor and contentedly slept.

In Enigma (2009), the movement relies on physical contact that seems thwarted. The dancers manipulate, resist, and repel one another as often as they stick together. When the connections get prolonged into duets, the dancers create oddly shaped lifts by gripping and shifting positions, without the preparation or steadying adjustments of ballet partnering. For this dance, a large overhead sheet of reflective fabric throws back the dancers’ reflections, which are distorted in the crinkles of the cloth.

Smoke drifted in and out of the space in Enigma, and in everything that followed. For CaDance (2009), two industrial-lighting fixtures hung over the space, and two big stage lamps beamed up from the floor behind the dancers. Smoke enhanced the shafts of light. Five men worked in vigorous faux combat, with stopped moves borrowed from martial arts and hip-hop, and vigorous twisty actions that sometimes matched a percussion score by Andy Pape, where arrhythmic drumming splattered against a fast, ticking underbeat.

A woman writes big capital letters in a continuous row on a stagewide blackboard in Kridt (Chalk) (2005). She might be imitating the phrasing of Peteris Vasks’s Musica Adventus, for strings. Later, someone drags a wet cloth across the chalkboard, partly erasing the letters.