In a world of curiosities, it's tempting to shrug off the incomprehensible. This is where Kreh Mellick's and Kimberly Convery's approach becomes a problem. Their drawings are bewildering, depicting circumstances and characters just beyond the realm of the logical, but it'd be wrong to take them as merely quirky meditations of two vividly imaginative women. There's simply more going on.

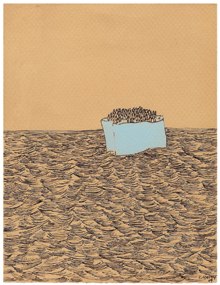

SURVIVALISM "Piece Out," by Kimberly Convery. |

Connected by a similar toolkit and process (and by friendship), Convery and Mellick are an inspired artistic pairing with major differences. Mellick's strength is her slightly abstracted portraiture (the women rendered fractious and the men monstrous), and here Convery relentlessly revisits a lemmings theme, where hundreds of microscopic, unidentifiable people seek a sort of refuge. Constantly refocusing the lens from Mellick's unsettling internal gaze to Convery's collective external narrative is one of the pleasures of the show.

With an implied landscape and very little discernible background, five of Mellick's gouache-and-pencil drawings are intimately connected. In "a tow," seven women in varying degrees of black dress form a queue under a blue stripe. Obliquely engaged with each other, their faces are expressionless. Two carry branches, one is topless, another appears to have fainted. In "a gather," a similar scene has unfolded; this time six women are governed by an ominous black cloud. In "small bellows," the women appear increasingly agitated as an ornate blimp floats overhead.

The delicateness of Mellick's hand can be seen in "Quiet Esther," a 2004 portrait of a thin and vulnerable young woman. Both here and with the women in black dresses, Mellick's palpable compassion rewrites the uniformly stoical faces on her female subjects. The men don't have it so good. In "Portrait D," a man veiled by a long beard holds a shotgun in his diminutive left arm. Though he may be a sportsman, Mellick's dark shadowing suggests a motive more terrifying and ignorant. Portraits "G" and "C" capture the same man with a Cardinal Richelieu moustache, the youthful hunger later contorted into a braying arrogance. In "Portrait B," a fatcat is caught with his gallantry down. Darkness be damned, these works are the most immediately stirring in the gallery.

Convery's "Safe Harbor" depicts hundreds of tiny people (rendered as microscopic cones) along the shore of a mountainous island with a desperation somewhere between that of a natural disaster evacuation and a Where's Waldo page. Whether fleeing, arriving, conquering, or merely enjoying themselves, the swarms of people flow in odd, incalculable patterns. "Peace Flags" employs an interesting ruse, as gargantuan trees growing out of the ocean are tied together by streams of flags as if to anchor them to the mainland. The bright blue in "Icy Cliffs" and amber in "Piece Out" exhibit how Convery's use of gouache can add emotional depth to her survivalist scenarios. On the occasions Convery strays from this theme, it's memorable. Her "Cloud Vignettes" and "Ladder Series" are tasteful exercises, and three typewritten and framed microfictions illustrate her artistic methodology.