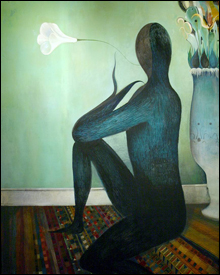

INTIMATE TALE “Murmura,” oil and enamel on panel, by Patrick Corrigan. |

It's probably safe to say Patrick Corrigan went through a surrealist phase. The thin vines and empty horizons that are his trademark evoke a folkier Joan Miró, and even his clearest, most literal images contain the unmediated symbols of a healthy subconscious delving. Experimental and imaginative though it may be, Corrigan's work just doesn't have a surrealist's defiant psychological splatter. Which is to say, he's done his research.

As explained by curator Daniel Pepice, the "Unconceptual" show witnesses Corrigan exploring two mythologies from very different origins. The first is borrowed from a strain of Chinese philosophy that conceptualizes the mind as a collection of storage systems, little boxes in which to house ideas.

The second comes from a Passamaquoddy tribal legend of mermaids spinning their hair into little walking creatures called (at least by Corrigan) "creeps," whose role, in the mythology, is to roam the world at the mermaids' bidding, telling the mermaids' tales. In this show the creeps are everywhere — sinewy, shadowy beings with thin, flickering limbs. If there's an overarching narrative to the exhibit, it's in the creeps' slow crawl towards subjectification, and the corresponding darkness that this evokes in Corrigan's work.

"Creep in a Tank" depicts a fitting intersection of the two mythologies. A creep is captured (or simply contained) in a pentagonal box. Two striking backdrops, like wallpapers shipped in from different continents, frame the subject. The creep is standing and well-defined, though it's impossible to decipher whether it's a prisoner or a prize. At the crossroads of the mind and the spirit, Corrigan doesn't show his hand.

In "Nat King Cove," a large oil-on-panel piece, a tiny creep is barely visible against the unilluminated side of a rather formless mountain across a body of water. Bright colors from the painting's perimeter pull the eye away, on the one side to a spectral, sage-like figure and the other to some dappled light below a monstrous expanse. Floating, multicolored balloons hover anxiously over empty terrain, buoyed by the same golden hoops used in body ornamentation. Death appears to be present.

"Storage System," "Spare Room," and "Carnival" witness Corrigan returning to the meticulous chambers of the mind. In the former, four boxy office-like items lie along imperfect planes in a clean room as if demanding proper assembly. "Spare Room" revisits the formula with a vocabulary of different shapes and color patterns in a domestic setting; a pyramid seems irreconcilable. "Carnival" shows a conceptual storage system at work, with two tiny creeps manipulating objects outside their box with a sort of utilitarian pulley system. A tropical green statue of a feline stands unapologetically near the right frame, asserting a familiar topical insignificance.

"Murmura" is the most affecting work: a large oil and enamel painting of a life-size creep (assuming human proportions, of course) in repose on an ornate rug. A tall vase suggests the creature is in a much larger compartment, a mystical storyteller in a modern-day home. The intimate tone is doubly present: Corrigan used the discarded feathers of seagulls to brush-stroke the finely black, amorphous body.