SELF-PORTRAIT A detail from Crenca’s Off the Wall. |

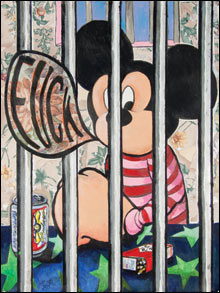

A SELECTION from the Free Mickey series. |

If you've been around the Providence art scene very long, you've surely heard the story. In the early 1980s, Umberto Crenca exhibited at the Antonio Dattorro Studio Gallery and the

Providence Journal panned his art as shallow and simplistic. Crenca and his pals felt it demonstrated how the art establishment didn't understand and excluded them. They responded with a 1982 manifesto, which laid out what became the founding principles of AS220, which Crenca and friends founded in 1985.

Now as AS220 is celebrating its 25th anniversary year, Crenca has filled the alternative space's galleries with "You Can't Call Your Own Baby Ugly," a retrospective of his art of the past decade or so (115 Empire Street and 93 Mathewson Street, Providence, through November 27). As AS220's artistic director over the past generation, Crenca, who is now 60, has led a team of determined artistic rascals who have been central to the so-called Providence renaissance. The twin foundations of the local art scene are RISD, one of the best art schools in the world which attracts top talent to Providence, and AS220, the downtown center which reaches out to the city, while also providing a crossroads in its café, galleries, studios, apartments, and concert hall, where ideas get exchanged, composted, and electrified. Not to mention that AS220 has become the launching pad where so many local artists have gotten their first public showing.

Crenca is the ringmaster, the great man at the center of AS220's great, generous, inspiring, welcoming carnival. But his own work is, well, another thing. Crenca's art is propelled by a prolific, relentless, try-everything-at-once drive that parallels AS220's founding uncensored, unjuried principles. He fills the back room at Project Space with racks and 15 binders stuffed with drawings. These and large paintings at the Main Gallery are an improvisational, free-association, automatic-writing, hallucinatory spew of melting eyeballs, teeth, stretched feet, skulls, breasts, penises, smiling cartoon freaks, and slithering things. You feel as if you've been jacked right into Crenca's brain. It's an anxious, frantic, unpleasant experience. Perhaps that's the point, but it's kind of a formal mess — so much going on, sloppy drawing, random color.

The surreal riffs on Mickey Mouse in Crenca's Free Mickey series feel somewhat sharper because Mickey gives him a focus and an architecture to hang onto. And there's always fun in seeing Mickey turned into a horned, fanged, scaly devil. One painting is a pretty straightforward Mickey painted like thrift store art — except Mickey has large human breasts. And his gloves seem like boxing mitts. And he's standing on a road that vaguely resembles labia.

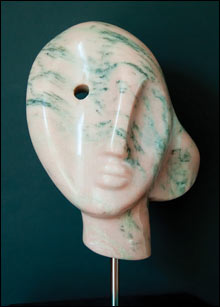

POLISHED CRAFT A marble head by Quinn. |

The best piece is Off the Wall at Project Space, a self-portrait made of various cut-out wood panels mounted off the wall with metal pipes. It's a field of floating images: a scorpion, Crenca's wife and AS220 property manager Susan Clausen; his father; his high school wrestling coach; Dattorro; disembodied eyeballs; melting, morphing grotesque figures; a bird; Geronimo; two ears merged together like a butterfly, a penis, and testicles with wings. In the center, four separate panels form Crenca's eyes, nose, mouth and trademark goatee. Crenca is still figuring the art out, but he retains the whatever-comes-into-his-head feel, while sharpening his painting chops and making the composition more coherent. Projecting the panels off the wall animates them. Crenca's public persona is of a tough, smart, charming rogue. Throughout the show, but particularly here in these sad, soulful eyes, he shows us a sensitive man, a wounded man, a searching man — a guy, like all of us, trying to make sense of all the contradictory forces churning inside us.