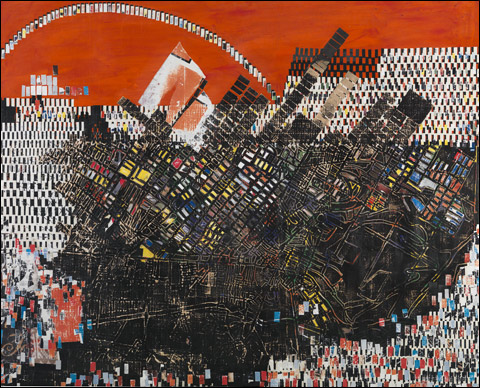

SCORCHED EARTH: Political messages aside, Bradford’s brilliance resides most in his crafty, physical ingenuity. |

Mark Bradford is one of those lucky artists who has figured out how to do one thing terrifically well. The artworks in his great Institute of Contemporary Art survey resemble transcendent Abstract Expressionist paintings of the 1950s, but they're actually elaborate, mural-sized collages built from pasted and battered and gouged layers of paper collected from billboards and posters that advertise movies, vodka, smartphones, cars, paternity testing.

His art looks and feels like an archæology of down-at-the-heel urban America. The compositions often resemble city maps; textures suggest urban decay. The advertisements are recycled from Los Angeles's South Central neighborhood, where he spent his first 10 years and now has his studio. The posters are from lampposts and even fences around empty lots where buildings were torched in the 1992 riots after four LA police officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King.

Bradford, who was born in 1961, is a 6'8" gay African-American artist and the winner of a 2009 McArthur "genius" grant. "I grew up in the '80s with the rise of AIDS, the rise of gangsta rap, the rise of crack cocaine, and the rise of the black faith church," he tells me at the ICA. "So, working in a hair salon, I was sort of at ground zero with all that stuff socially. My mother was a hair stylist, and I was a hair stylist. So for me socially, the impact of that stuff was so great in the black community, and so personal, intimate for me. What I really understand now looking at the work, I think that it was too traumatic. I think that it was simply traumatic. I went to Europe for 10 years. I went to school [CalArts]. And just like with Abstract Expressionism, where many of them came from Europe after the war and they had to sort of deal with the trauma through abstraction, I use the tenets of abstraction to actually point to things in the social condition."

This represents a switch. During the past century, African-American artists often made realist art to address directly the oppression and struggles of black America. But in an era when the (white) art world was focused on abstraction, this realism was one more way in which they became marginalized.

Bradford's show (which was organized by the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University) opens with somewhat uninspired, Agnes Martin–style late-Modernist abstract grid collages from the early 2000s. He's aiming for social commentary with titles like Enter and Exit the New Negro (referring to Alain Locke's 1925 civil-rights writings) and Strawberry (slang for female crack addicts) and materials like permanent-wave endpapers. How much social content you find in these collages depends a great deal on how much you believe titles determine the meaning of artworks.