A SECOND LOOK: Pasternak’s novel was always too big for just one translation. |

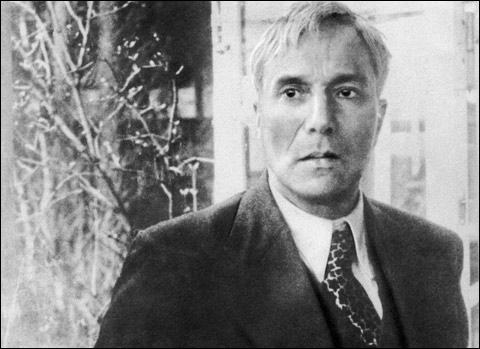

More than a half-century after its first appearance, Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago is just now getting its second translation into English. For all that Pasternak garnered a Nobel Prize (which he was compelled to refuse) for his epic novel, it's best known to Americans via the 1965 MGM film starring Omar Sharif and Julie Christie. And while the likes of Anna Karenina and The Brothers Karamazov rack up new translations, Zhivago languishes in obscurity. This new version by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky — who most recently, in 2007, gave us their War and Peace— won't change that.

Not that any translation really could. Zhivago is not a novel in the usual sense. Pasternak's sensibility is closer to Tolstoy than to Dostoevsky, but even by War and Peace standards, this is a book about ideas rather than characters. It's the novel as essay, with discussions of philosophy and religion tucked in amid the carnage of World War I and the Russian Revolution. It's the novel as a poem whose subject is Moscow (the "holy city," as it's called on the final page), or Mother Russia, or human destiny. In that sense, "The Poems of Yuri Zhivago" that form the coda are the crux of the novel, the rest of which is like a prose gloss on them. "Winter Night," with its "Crossings of arms, crossings of legs,/Crossings of destiny," is the key: Zhivago, on his way to the Sventitskys' Christmas party with his future wife, Tonia, sees the candle burning in Pavel Antipov's window but doesn't realize that Pavel's future wife, Lara, is his, Zhivago's, fate.

Pasternak had his own destiny, Olga Ivinskaya, the inspiration for Lara, though he declined to leave his (second) wife for her. Zhivago is in part the author's rationalization: Zhivago loves Tonia, but he and Lara are one. There are such crossings of destiny (not all fully realized) throughout the novel, woven from the paths of "minor" characters like Misha Gordon, Nika Dudorov, and Mademoiselle Fleury as well as the ones the film made famous. Pasternak could have taken as his starting point the final paragraph of War and Peace, with its recognition of "a dependence of which we are not conscious."

This new version is of a piece with the translators' previous efforts (which include Gogol, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov as well as Tolstoy): scrupulous in its pursuit of accuracy but not always successful in capturing the rhythms of graceful English. This sentence is from the 1958 translation by Max Hayward and Manya Harari:

The horses were like horses the world over: the shaft horse pulled with the innate honesty of a simple soul while the off horse arched its neck like a swan and seemed to the uninitiated to be an inveterate idler who thought only of prancing in time to the jangling bells.

And here's what Pevear and Volokhonsky offer:

But the horse pulled like all horses in the world; that is, the shaft horse ran with the innate directness of an artless nature, while the outrunner seemed to the uncomprehending to be an arrant idler, who only knew how to arch its neck like a swan and do a squatting dance to the jingling of the harness bells, which its own leaps set going.