The patients assemble for another group-therapy session. "Now choose a partner," says the invisible therapist in an ominously cheerful voice. "Make contact and throw your energy." After an uncertain pause, they work themselves into a huge game of Indian clubs flying in all directions, and then an even more manic jamboree of bodies flying, diving, air-somersaulting, and falling safely into the arms of their companions.

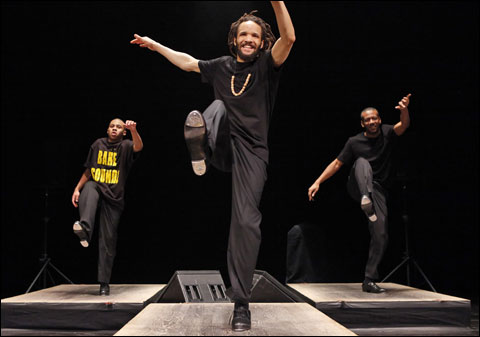

FASCINATING RHYTHM The longer you watched Savion Glover, the deeper he got. |

Savion Glover's new show, SoLo in TiME, is a feast, a chance to live with genius for a solid hour and a half. That's what happened Saturday night at the Opera House, when Glover, possibly the world's most accomplished rhythm dancer right now, came to Boston courtesy of the Celebrity Series and CRASHarts. He had great associates with him: tapper Marshall Davis Jr. and the band Flamenkina (percussionist and singer Carmen Estevez, bassist Francesco Beccaro, and guitarist Gabriel Hermida). But it was Glover who commanded the stage, and the longer you watched him, the deeper he got.

Soloist and star, he gives performances that are more like classical recitals than rock concerts. He doesn't behave like a big personality — no displays of temperament or fancy histrionics. He dances with and to his musicians more often than he projects to the audience. Yet you feel some kind of intimate contact with him. After he's acknowledged everyone in the performance including the stage manager, the lighting guy, and the people who handle the sound, as well as noted dancer mentors in the house, present and departed (Dianne Walker, Jimmy Slyde, Leon Collins), he seems to know all the rest of us who are there. In the bows, he extends his arms and hugs us to his chest. I don't mean he's one of those icky warm-and-fuzzy types. If anything, he's an extremely introverted dancer. But he's got it all stored up inside himself and incorporated in the energy of his dancing.

What I like so much about the way Glover puts together a show is his generous sense of time. Whether it's jazz, classical music, or, as in this case, flamenco-Latino fusion, he isn't content with a chorus or two of a number. Each piece goes on for a long time, dancer and musicians exploring, trading ideas, branching out, changing tempos, returning to a basic rhythm, until all the players just come together and stop. Even then, the possibilities may not be exhausted. Glover pauses, maybe walks around drinking some water or exchanging words with one of the musicians, and thinking. Then, with a new idea, he sets a rhythm and they're off again. Dressed in black pants and a floppy gray cardigan over an orange-red T-shirt, this thin, contained man with a big topknot of dreadlocks seems all legs, his mind and motor totally absorbed in a universe of rhythms.

When you first hear Glover, you think his dance is nothing but speed, the fastest and most clearly distinguished steps a person can produce. These steps group into phrases of loud and soft beats, syncopations, suspensions, small pockets with impossible numbers of taps crammed into them, long melodic stretches of textured phrasing. He uses all the surfaces of his feet in every imaginable way — fluttering, paddling, clicking with a toe behind him, weaving with both feet crossing in front of him, sudden isolated stomps and then stomps repeating in triplets, his leg clanging off the floor.