JUST A CHESS NERD? Not according to Barbra Streisand. |

Bobby Fischer was

(a) a former world chess champion;

(b) the greatest chess player who ever lived;

(c) an idiot savant;

(d) a prodigy;

(e) a megalomaniac;

(f) anti-Semitic;

(g) paranoid;

(h) the guy Barbra Streisand had a crush on in high school;

(i) all of the above. Correct answers? Definitely

(a),

(e),

(f),

(g), and (!)

(h), and quite possibly

(b), but not

(c) or

(d).

In other words, he was a complicated guy. And Frank Brady's new biography tries to simplify the confusing material into an endgame — Fischer died in January 2008, of kidney failure, while in exile in Iceland — that we can all understand. He's hampered, however, by poor choices in the opening. The decision to call Fischer "Bobby" and everyone else by last name leaves his objectivity en prise. And though in his "Author's Note" he asks forgiveness "for my occasional speculations," he speculates as to Fischer's thoughts more than occasionally, and often simple-mindedly.

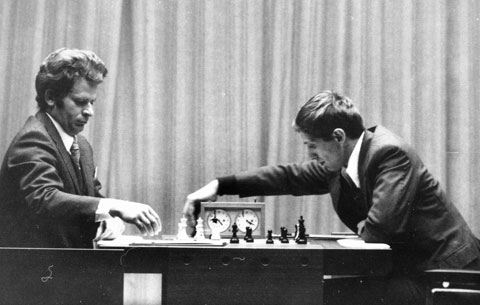

Not that Fischer is an easy opponent, er, subject. He was born in Chicago in 1943, homeless mother Regina a Swiss-born Jew, father unknown. He grew up all over the Midwest and West before his mother settled in Brooklyn. He was a chess prodigy of sorts, but no Anatoly Karpov (who succeeded him as world champion in 1975): what made him great was his ability to learn from his defeats and his determination not to lose again. He spent the '60s railing against Soviet plots to keep him from challenging for the world championship. In 1972, he broke through, defeating Boris Spassky in the historic match in Reykjavík.

But the beginning was also the end: his exorbitant demands for the conditions of his 1975 title defense were rejected by FIDE (the world chess governing organization), and he didn't play an official game again till 1992, when he agreed to a lucrative rematch with Spassky in Slobodan Milosevic's war-ravaged Serbia. In between, he lived mostly in LA, and sometimes in flophouses. Post-Belgrade, he couldn't return to the US (where he was wanted for income-tax non-payment, and also for violating UN sanctions by traveling to Serbia); he lived in Hungary (visiting with the chess-champion Polgár sisters and pursuing a 17-year-old girl he wanted to marry), Japan (where he married — we think — Miyoko Watai, the president of the Japanese Chess Association), and, finally, Iceland. Along the way he indulged in radio broadcasts (that went online) wherein he blasted Jews, Russians, and the US government and eventually applauded the 9/11 attacks. He remained firm in his belief that he was still world champion. Chess, however, went on without him.

As the president of the Marshall Chess Club and the founding editor of Chess Life (and the author of a previous bio, Bobby Fischer: Profile of a Prodigy), Frank Brady should at least have a handle on Fischer's chess persona, but not a single game appears in this book, and the intricacies of the 1962 Curaçao Candidates' Final (Fischer played poorly, then claimed Soviet collusion), the 1967 Sousse Interzonal (after protests and forfeits, he was expelled), and the 1971 Candidates' Final game he lost to Tigran Petrosian (head cold!) go unannotated. (Try Wikipedia.) Instead, Endgame's winning strategy is its portrait of Fischer off the board as a man who, in addition to demanding that the toilet seat in his Belgrade villa be raised one inch, could discuss Candide and Animal Farm and The Picture of Dorian Gray and sing the refrain of the Smugglers' March from Carmen. And yet in the annals of chess legends, he remains a line still largely unexplored. The search for the real Bobby Fischer goes on.