POINTED PIZZAZZ You could see The Cold Dagger as a kind of yin/yang counterpoint, calmness balancing aggression. |

Life is a struggle, according to the four works on Friday's program by Beijing Dance/LDTX (presented by the Celebrity Series at the Tsai Performance Center). Consensus may eventually prevail, but conflict seems the norm. Rebels get punished; the group offers balm for the discontented.Beijing Dance/LDTX is the latest creation of artistic director Willy Tsao, who's fostered the cause of modern dance in Hong Kong and then mainland China over the past 30 years. What was once a maverick of the performing arts has become a respectable part of training programs and performing companies. Beijing Dance/LDTX doesn't rely heavily on traditional Chinese dance. It does reflect international contemporary dance styles, as well as martial arts.

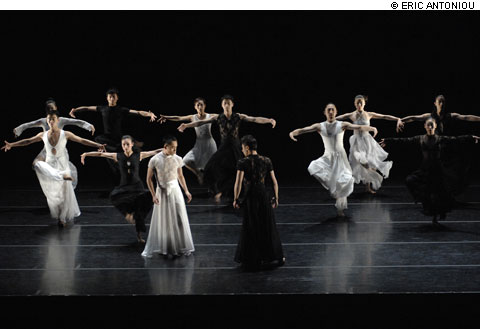

Although the movement has the physical pizzazz we expect, all the pieces I saw seemed as concerned with conveying themes of community as they were with flashy performing. Movement is meaningful, expressive, in the old modern-dance sense. In The Cold Dagger, an excerpt from an evening-length dance, two men engage in fierce hand-to-hand combat, flanked by the other dancers doing soft tai-chi-like patterns. You could see this as a kind of yin/yang counterpoint, calmness balancing aggression.

In this contest and several others, men fight each other with big, circling moves, locking arms in order to fend each other off or hoist the opponent away. When the men partnered the women, the sides were less equally matched. In Solitude in Numbers, there were four couples and four chairs. People took possession of the chairs in varying ways, but the real contest was between the couples. Grabbing her from behind, around her waist, her hips, under the arms, the man would throw the woman around violently. She'd struggle sometimes, but more often she'd submit to this rough handling by going still. Sometimes she'd try a countermove, but only in order to avoid being shoved into worse contortions. The dance ended with a woman standing over a man who was doubled up in a coughing fit while yet another abusive duet was going on in another part of the space.

October (to that section of Tchaikovsky's piano piece The Seasons) was a duet of total accommodation. Side by side, a man and a woman went through a long series of mime gestures, very clear and in unison. Although they didn't actually look familiar, the gestures suggested the actions of a life: farming, cooking, keeping house. Whatever these two were doing, their moves were identical, not complementary, until he picked her up and they engaged in a brief duet. The woman (Song Tingting, who was one of the choreographers of the piece, with Liu Bin), kept moving with astonishing fluidity no matter how she got shifted and twisted around by her partner, Xu Yiming. After this joint interval, they returned to their unison task.

For some reason, deputy artistic director Li Hanzhong and dancer Ma Bo took on Igor Stravinsky's Le sacre du printemps, which has been choreographed innumerable times since its infamous premiere by Vaslav Nijinsky in 1913. Their All River Red used the music mainly for effects — explosive energies, mysterious moods — and ignored its scenario. I saw the dance as a series of dramatic events. People move around the stage in short, confused runs. They carry cloth shoulder bags, which they later spread open and use as scarves, bindings, shrouds, ropes. A woman is tied up and blindfolded and carried off, but that's the end of her victimization. Men and women dance together, the men aggressive, the women passive.