THE CONSTANT SHIFT OF PULSE Doug Varone's piece was staged for 19 dancers at Boston Conservatory Dance Theater— and it was explosive. |

Doug Varone's 2006 The Constant Shift of Pulse is a modern dance classic of recent vintage: fast, death-defying, and passionate about nothing but the movement. It was given a marvelous performance Thursday night by the Boston Conservatory Dance Theater as part of "Triple Play," the second program under the dance department's new chair, Cathy Young.Hubbard Street Dance Chicago brought Varone's piece to Boston three years ago, but this time around it made a bigger impact. Hubbard Street performed the work with a modest 12 dancers. Staged for 19 by Natalie Desch and the Conservatory's Leslie Shafer Koval, the dance was explosive. John Adams's dense two-piano "Hallelujah Junction," played live by Yu-Hao Chen and Juliana Chalsen, galvanized the dancers as no recording could. Adams's post-minimalism doesn't lure the choreographer into formalist lines and groupings. Instead, the music releases its pent-up energy into movement.

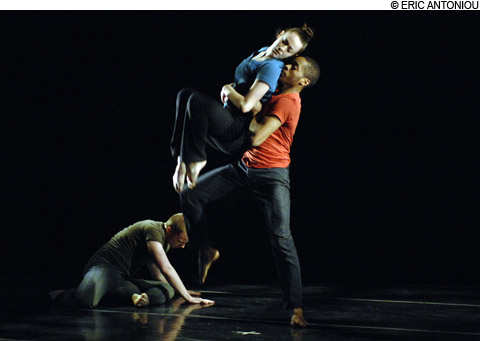

Varone's big bursts and waves of surging, subsiding, and renewing activity invokes the dynamic of a crowd— unruly but momentarily purposeful. The dancers fling themselves into stretched-out, dirt-devilish spins, slides, dives. They erupt out of nowhere to streak across the space and suddenly run smack into other people and topple to the ground. In the slow section, their almost-random contacts — shoulder to back, head to fist — lead them into lifts and tumbles and contented pileups. Their fragmentary encounters are nothing like the contemporary dance's contrived simulations of erotica. In their gender-neutral jeans and T's, they might have been discovering something more grounded and supportive than sex.

Daniel Pelzig is well-known around Boston as a ballet choreographer, but he's been working in opera and commercial theater for a while. His Trio in A Minor, choreographed for the Conservatory students, premiered on Thursday night. It seemed a lot more substantial than other pieces made to show off the students' classical training that I've seen in the past. Pelzig deftly arranged Tchaikovsky's set of variations on a theme (played by Rui Urayama, piano, Egle Jarkova, violin, and Edevaldo Mulla, cello) to feature several of the dancers while retaining the traditional setting of soloists and corps de ballet.

The dance started out looking classical, with the 10 women in pointe shoes and tulle ballet dresses. (Costumes were by Susan Slack.) At first the five men looked incongruous in their chinos and flesh-colored muscle shirts. But even within Risa Yokoi's introductory solo there were modernistic gestures, and the dancers went on to augment the vocabulary with one-handed cartwheels, knee-walks, sprints, and back rolls. For the last variation all five men partnered Evelyn Toh, and each other, against a backdrop of twinkling stars. I thought of Jerome Robbins's romantic ballets — classical but anchored to the real world of dancers.

Curiously, the formal patterns of Cathy Young's jazz piece Zero Cool (1998) were a less easy fit for the dancers than either of the other two works. At least on the first night, they seemed to be groping their way into the movement and the Duke Ellington music, but with encouragement from their pals in the audience, they began to get down withit.